Nativeness and First Principles of AI

TL;DR: First Principles of AI are about information volume; What follows AI First Principles is AI-native; Multi-modal intelligence is the key

⚠️ This blog is approximately 25,000 words long. If you want AI to summarize the blog and skim through it, you might find unexpected results.

As for debugging, you’ll need to read at least up to the example of the LLM Voice Conversation System :)

A bit of detour

If the cover image is too dark and scared you, my bad. It features a character from Jujutsu Kaisen that I watched in 2023 — Kokichi Muta.

Mechamaru or its operator—Kokichi Muta

His background doesn’t matter, but what’s relevant here is his curse and talent. His curse is a fragile body, but as the saying goes, “When God closes a door, He opens a window.” His talent lies in “mechanical manipulation” and exceptional stratagem.

As GPT-4 emerged and I interacted with it more and more in daily life, research, and work, my impression of it shifted from vague to clear. It reminded me of the image above (and Mechamaru and Kokichi Muta). If you’re particularly familiar with GPT-4 and also know Jujutsu Kaisen well, you might find this amusing. However, the intersection of these two groups of people is relatively small, so I’ve digressed a bit here. Many parts of this blog will subtly echo with this character. But, I just felt compelled to include him in this post, so you can still understand the content even if you’re not familiar with him.

To learn more about Kokichi Muta, you can check here or here.

If you’re also a fan of Jujutsu Kaisen, here’s an interesting thought experiment I came across: If Kokichi Muta were to represent GPT-4, would his motivations and ending align with those of AGI?

I don’t have the answer, but you might have some interesting thoughts.

Abbreviation Glossary

For brevity, the article uses some “common” English abbreviations. “Common” may not mean the same for everyone, so here’s a glossary.

| Abbreviation | Full Name |

|---|---|

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AGI | Artificial General Intelligence |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| ASR | Automatic Speech Recognition |

| CV | Computer Vision |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| GPT | General Pretrained Transformer (Now “GPT” is a concrete term) |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| OS | Operating System |

| SD | Stable Diffusion |

| TTS | Text to Speech |

Questions and Quasi-Answers

I often see many people asking the following questions or similar ones:

- What qualifies as AI-native?

- Where is the boundary between model and application layers?

- Another straightforward translation is: Where does OpenAI draw the line?

A previous blog topic I considered was: Why isn’t Rabbit R1 AI-native?

Recently, when I put these questions and topics together in my mind, I realized they all essentially ask the same thing:

“What are the first principles of AI?”

Once we understand the first principles of AI, the rest of the questions become easy to solve:

- Applications that follow the first principles of AI are considered AI-native. Abilities directly stemming from AI’s first principles are AI’s native capabilities, marking the boundary of the model layer.

- Abilities that cannot be directly derived from AI’s first principles should be implemented at the application layer, which OpenAI would not touch.

- Similarly, AI-native hardware should align with AI’s first principles. Rabbit R1’s design, rooted in outdated AI hardware concepts, does not adhere to these principles, making it non-AI-native.

What are first principles?

It seems everyone knows what first principles are, as if we learned them in high school. But it seems no one can clearly define them. I’m also unsure (what they’re talking about), so here’s my understanding and definition:

First principles involve logically deducing or deconstructing complex logic or combinations back to a few basic components. This tracing process requires constantly examining the necessity of various elements, removing the unnecessary or derived ones, until what remains is indivisible. These indivisible basic components are the first principles. Alternatively, we could approximate them with “axioms” from first-order logic. We should teach first-order logic in high school, not in graduate courses 🐶

As for what counts as “indivisible” or how is a truth “self-evident” (see the meaning of “axiom”)? That’s a question!

The First Principles of AI

So, what are the first principles of AI? I believe it’s “information volume”, which refers not only to the amount of information but also to its quality and the fidelity of its transmission and conversion.

Those familiar with NLP and CV in deep learning should already be quite acquainted with the concept of “information volume,” but I still want to reiterate some rules of thumb derived from DL practices:

- Given the same quality, more data is better — the more information, the better.

- LLMs now use the entire internet’s corpus for training.

- SegmentAnything elegantly improved semantic segmentation performance through data brute force.

- With the same amount of data, the quality should be as high as possible — the higher the quality, the better.

- Exceptionally performing small models like Phi-2 demonstrate the importance of corpus quality.

- Various fine-tuned models of Stable Diffusion are also examples.

- In terms of data representation and model design, minimize heuristics — information flow should reduce heuristics, allowing the model to learn on its own, preserving as much information useful for the model as possible.

- Countless examples have proven this point, two classic ones being the deep CV started from AlexNet and DL-based NLP.

- The new bible “The Bitter Lessons”, in its essence, is also to minimize heuristics.

- In today’s DL era, this principle is too obvious. Many students who entered the field directly through DL, without learning statistics-based machine learning, would naturally agree.

For those not familiar with DL, the first and second pieces of experience are relatively easy to understand, similar to how reading more books makes one smarter, but it’s also important to sift through and select valuable, meaningful knowledge while reading. Regarding the third piece of experience, I’ll provide more examples in a moment to help explain. For now, let’s use an analogy. The learning and growth of us humans often involves making our own choices. Although influenced by teachers and parents, ultimately, our understanding of the world and life comes from ourselves. Of course, there are examples where parents and teachers overly intervene and design. Imagine a person whose understanding of everything is entirely based on their parents’ views. This person might live well, but we wouldn’t consider them very intelligent. Models with excessive heuristics are like such a person.

You mentioned what AI’s first principles are, but how did you deduce them? You mentioned what they are, but not why.

Indeed, you got me! Because the field of AI is so broad, with numerous theories and a lot of noise and hype, it’s difficult to deduce from very general concepts or questions. General concepts or questions are akin to asking, “Does Sora follow AI’s first principles?” “What’s the relationship between AI’s first principles and AGI?”.

My understanding of AI’s first principles comes from various practical examples I’ve encountered, so I’ll introduce these examples in detail later. While discussing these examples, I’ll attempt to analyze their underlying issues. Hopefully, after I’ve covered these, you’ll see the commonalities between them. These commonalities, pushed one step further, bring us closer to AI’s first principles.

This way, you don’t need to blindly follow my reasoning but only believe in my examples. Starting from the examples and trusting your own reasoning, you can reach the same conclusion (I hope).

The Significance of AI’s First Principles for System Design

The concept of AI’s first principles has been briefly explained above, but what does it mean for system design? Here, “system” refers to AI models and larger systems comprised of AI models. I’ll give a few examples and my thoughts. Note that these examples are not in chronological order.

The first example is a tutorial by Andrej Karpathy a few days ago, “Let’s Build the GPT Tokenizer Together.” Those who follow AI news closely, especially LLMs, have probably watched this tutorial (I guess). If not, I highly recommend checking it out! Andrej is a legend, and his tutorial is both entertaining and easy to understand.

In the tutorial, he mentioned that LLMs sometimes exhibit strange behaviors, specifically these eleven issues:

- Why can’t LLM spell words?

- Why can’t LLM do super simple string processing tasks like reversing a string?

- Why is LLM worse at non-English languages (e.g. Japanese)?

- Why is LLM bad at simple arithmetic?

- Why did GPT2 have more than necessary trouble coding in Python?

- Why did my LLM abruptly halt when it sees the string “<|endoftext|>”?

- In fact, I broke GPT when trying to get help to translate this blog from Chinese to English due to this very token.

- What is this weird warning I get about a “trailing whitespace”?

- Why the LLM break if l ask it about “SolidGoldMagikarp”?

- Why should I prefer to use YAML over JSON with LLMs?

- Why is LLM not actually end-to-end language modeling?

- What is the real root of suffering?

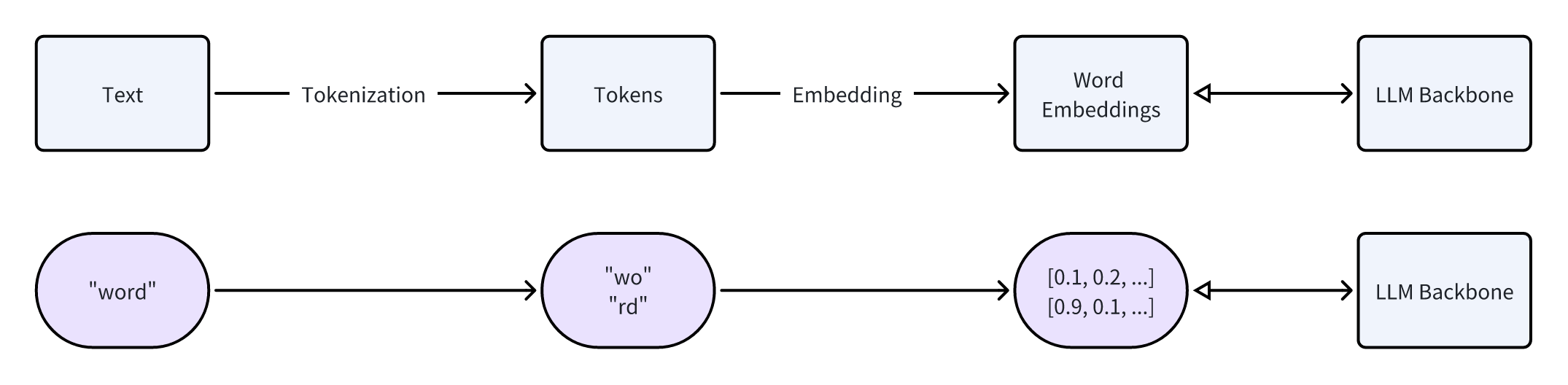

These issues ultimately stem from tokenization and tokenizers. Tokenizers are a crucial part of LLM design involving significant heuristics. Tokenizers divide words into smaller parts or combine them into larger parts, called tokens, such as splitting “word” into “wo” and “ rd“ or combining “LGTM” into a single token due to its high frequency in corpus. These tokens are the basic units LLMs work with. Languages like Chinese require even more complex tokenization. I won’t delve into the details here, but Andrej’s tutorial is a great resource.

Didn’t Andrej say the tokenizer is trained? Why is it considered heuristics?

The term “training” has been somewhat overloaded. In reality, the training of a tokenizer can only be considered iteration. The difference between “iteration” and “training” is out of scope here, but simply put: the iteration of a tokenizer doesn’t involve updating model parameters, whereas “training” should refer to the process of continuously updating model parameters.

Moreover, if you carefully watched the tutorial, Andrej mentioned at the beginning that the training of the tokenizer is part of corpus preprocessing; and in the latter part of the tutorial, he listed many rules introduced by researchers during the “training” of the tokenizer. These all indicate that the tokenizer is a product of heuristics.

Andrej gave an interesting example of some strange compound words, such as “SolidGoldMagikarp.” This word doesn’t have any obvious meaning, but the tokenizer treated it as a single token, possibly because it was the username of a Reddit user who posted a lot in the corpus for the iteration of the tokenizer. Large models process tokens by converting them into embeddings, then continuously updating each token’s embeddings and the large model’s own parameters during training.

What are embeddings?

Language models can’t directly process tokens; they work with the corresponding embeddings. An embedding is a series of numbers, such as the token “you” being represented by an embedding like [0.1, 0.2, 0.15, ……]. The length of this series is predetermined, usually in the thousands.

During the training process, large models continuously update embeddings, which essentially represent the model’s understanding of a particular token, though humans can’t interpret the meaning of these numbers. Each token’s embedding starts as random numbers, and only after the model begins learning and the embeddings are updated do they eventually represent the model’s understanding of a token.

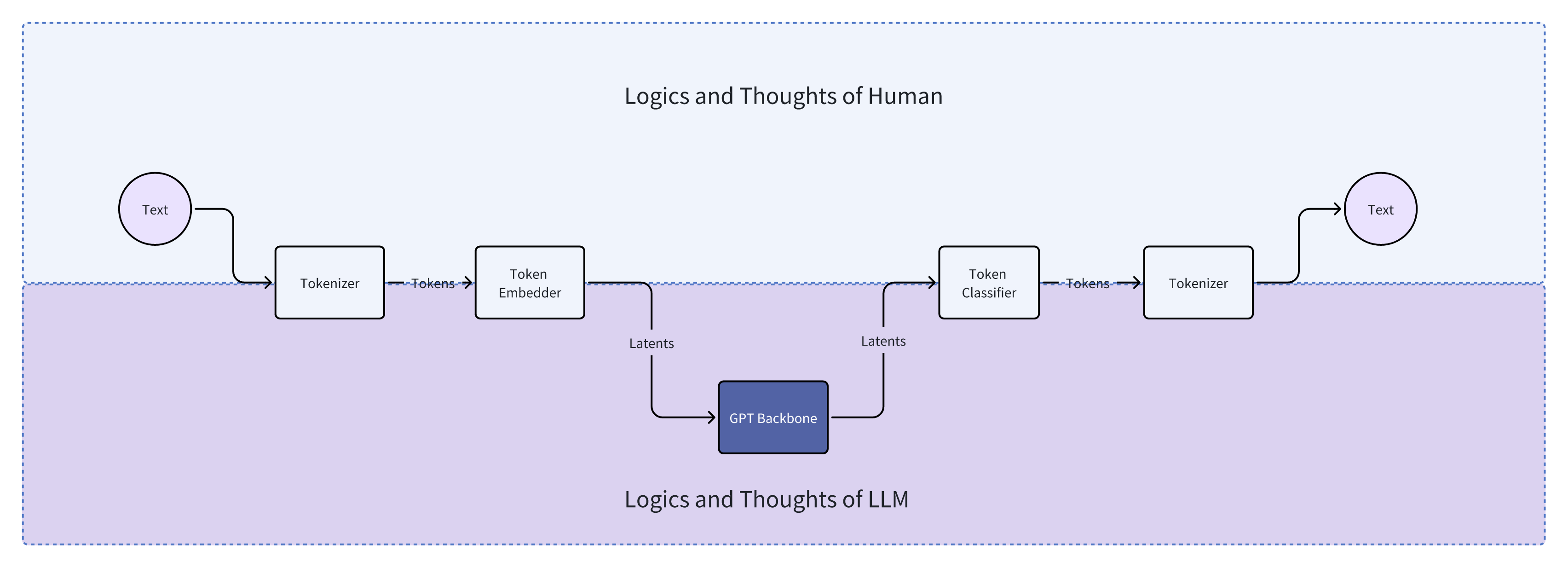

The overall process is illustrated below, with the top half showing the process and the bottom half providing an example. The double arrows indicate that embeddings are input into the model for forward processing and can also be updated in the backward pass.

However, the corpus used for training the large model might differ from the one used for iterating the tokenizer. In such cases, although the large model has embeddings for “SolidGoldMagikarp,” it has never encountered this token during training, so the embeddings for this token have never been updated and remain the initial random numbers. The large model can’t understand these embeddings, which remain random, leading to strange behaviors when encountering these tokens.

In this example, at least three aspects involve (or can involve) heuristics:

- Which strings are considered a single token?

- For instance, we can manually add the string “<|endoftext|>” as a token.

- Settings, iteration data, and strategies for the tokenizer

- One example Andrej mentioned is using Sentencepiece to iterate the tokenizer, allowing the replacement of rare words with the “<unk>” token, where “unk” stands for “unknown character”.

- Regarding data for iteration, if the corpus used for iterating the tokenizer doesn’t include Chinese, then the tokenizer is doomed to perform poorly in processing Chinese.

- Additionally, how the tokenizer handles numbers directly affects LLM’s mathematical abilities.

- Data used for training the LLM: Some large English models that hack benchmarks start by removing non-English data from the training set, which, although cost-saving, cripples the model’s ability to understand languages other than English, even if it’s intelligent enough.

Question 1: Discrimination in the Training of Large Model?

If a product manual is only available in English, and the manual’s authors say, “We only consider English-speaking users,” would you feel discriminated against? Similarly, when you see statements like “we removed the non-English part of the dataset/corpus” in LLM training reports or papers, would you feel discriminated against?

There’s also a subtler case: if the corpus used for iterating the tokenizer is 99% English, and the iteration settings are such that rare words are filtered out and common word coverage is 99%, meaning words appearing less than 1% of the time are replaced with “<unk>”, would you feel discriminated against?

Question 2: Has AGI Arrived?

This example can lead to many extended discussions, but let’s get back on track to the main topic, which is the connection between this example and AI’s first principles. The importance of data volume and quality in LLM examples need no further explanation, but what we need to consider is the third point:

Information flow should reduce heuristics, allowing the model to learn on its own, preserving as much information useful for the model as possible.

If we could eliminate the tokenizer, taking every byte as a token, then most of the eleven issues mentioned by Andrej could be easily resolved. These issues remain primarily due to tokenization and the heuristics within it. I could even say this hinders the arrival of AGI.

In this example, the “system” refers to the combination of iteration data for the tokenizer, the tokenizer itself, the LLM training data, and the LLM. On the surface, we traced the root cause of engineering issues from the issues mentioned by Andrej back to the tokenizer. But what’s the essence of the problem? I believe it’s heuristics. Humans tend to believe our understanding of the world is correct and effective, and we often think the world is comprehensible and orderly. Thus, we often incorporate our thought processes into our creations. However, we don’t fully understand our own mind, let alone fully comprehend the world. Even in the case of Go, our understanding might not be as profound as AlphaZero, which was trained from scratch without studying game records. Actually, much of our thinking is “chaotic” (as described in Thinking, Fast and Slow, a great book).

While not countless, many examples have shown us that there are many ways to understand the world. Rich Sutton’s The Bitter Lesson also summarizes a similar conclusion, which is that AI’s way of understanding the world doesn’t necessarily have to conform to ours or our heuristics. We need to reduce heuristics to train more powerful AIs.

But wait, couldn’t we design a perfectly perfect tokenizer to solve these problems?

This question is similar to one in the history of NLP: “Can we model and understand language with rules?” Since language is a manifestation of our thinking, the question can also be reframed as “Can we model and understand our thinking with rules?” My answer is “Partially, such as in mathematics, but most cannot be defined and explained with rules,” which translates to “You can try to design a perfect tokenizer for some specific cases, but a universally perfect tokenizer does not exist.”

> Information Flow — The Example of the LLM Voice Conversation System

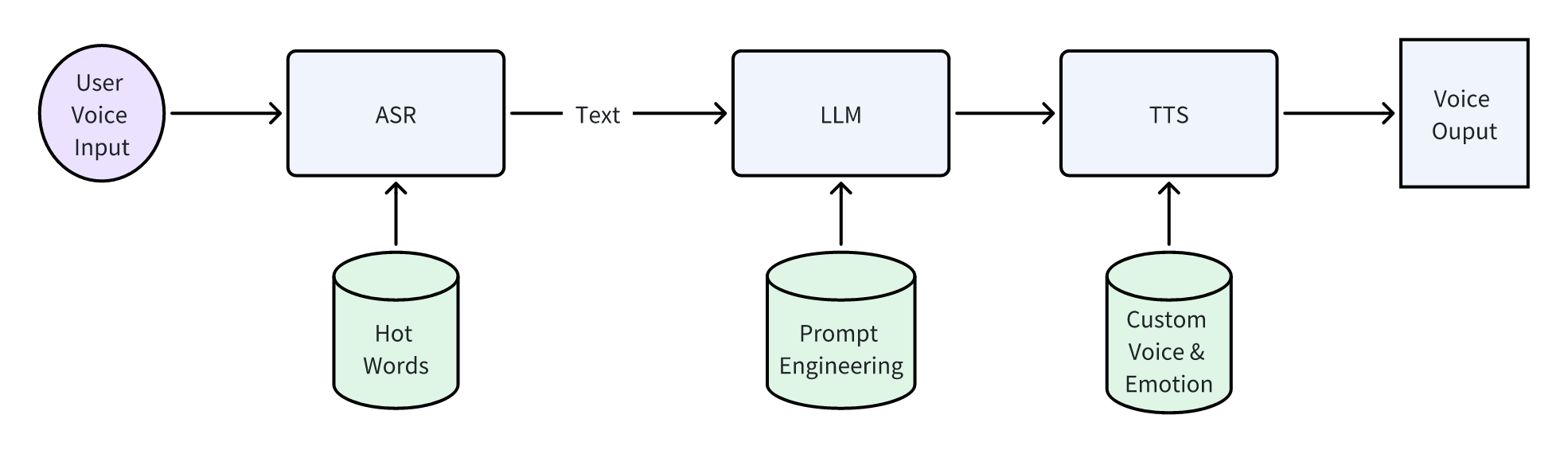

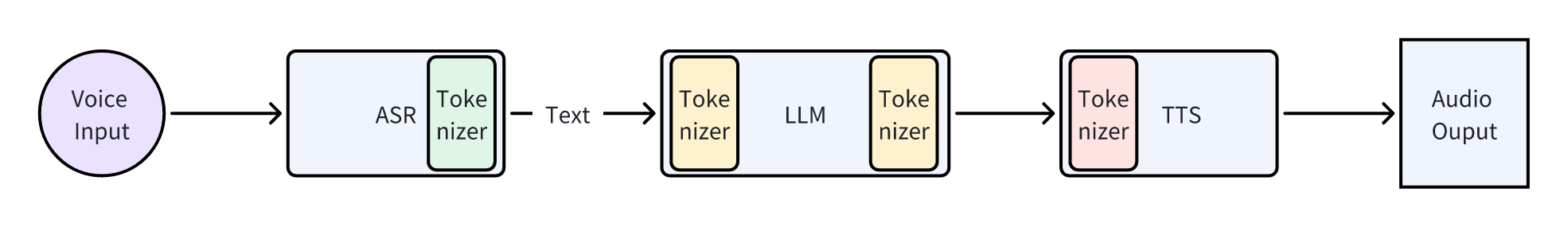

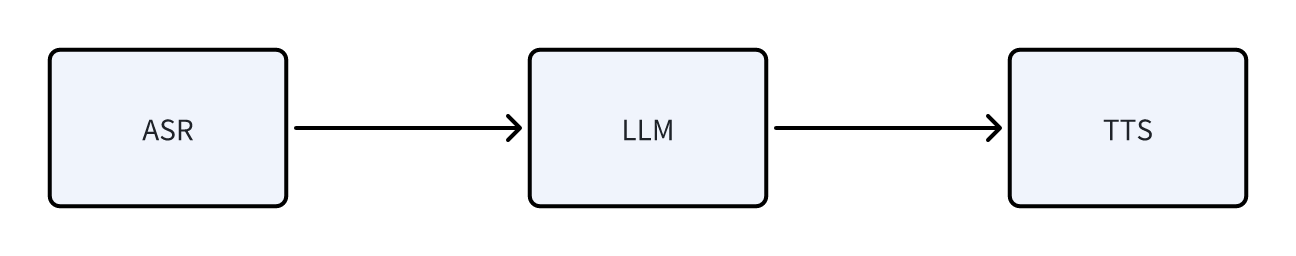

Another example is the LLM voice conversation, which might be easier to understand but is actually more complex. This is also a problem I’ve encountered: how people can converse with LLMs through voice. Conversation is bidirectional, meaning people should be able to speak, and LLMs should also be able to speak in response. If you’re familiar with existing AI blocks, your first thought might be: (Isn’t this simple?) Use ASR to convert human speech into text, send the text to the LLM, and then use TTS to convert the LLM’s text response into speech.

At first, mine is the same. First, how do we know when a user wants to converse with the LLM? Well, since I’m working on a proof of concept, let’s assume users will press a button to initiate a conversation with the LLM. ChatGPT does the same after all, so assumption justified 🐶 Then comes speech recognition. The accuracy of ASR is fairly decent, though it might mishear some words, so I thought adding hot words/common words should fix that (I guess?); LLM is not a big issue. I use Dify for prompt engineering, and as long as ASR’s results aren’t outrageously unfaithful, LLM has some ability to correct errors given the context; Finally, text-to-speech. Many cloud providers offer TTS services, so I just need to send the LLM’s output to a server. Thus, the conceptual pipeline of the entire process looks something like this:

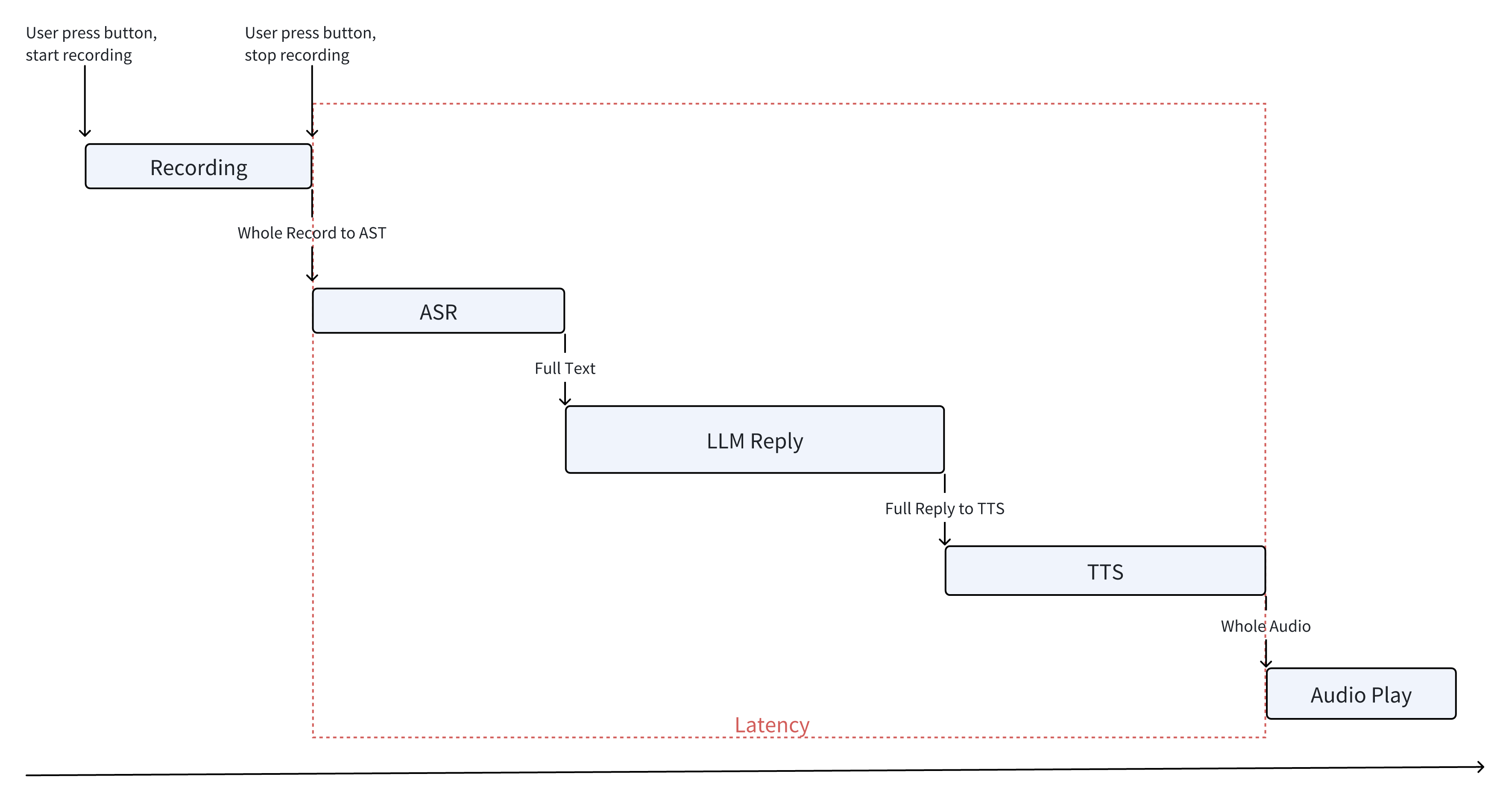

Seeing this diagram, those who have learned from the first example’s lessons might start to feel something is somewhat amiss. However, I didn’t see any problems at the time; it seemed like a standard solution. Let’s for now set aside our reservations and assume this is the right approach and implement it accordingly. Below is the flowchart of my first version of the implementation.

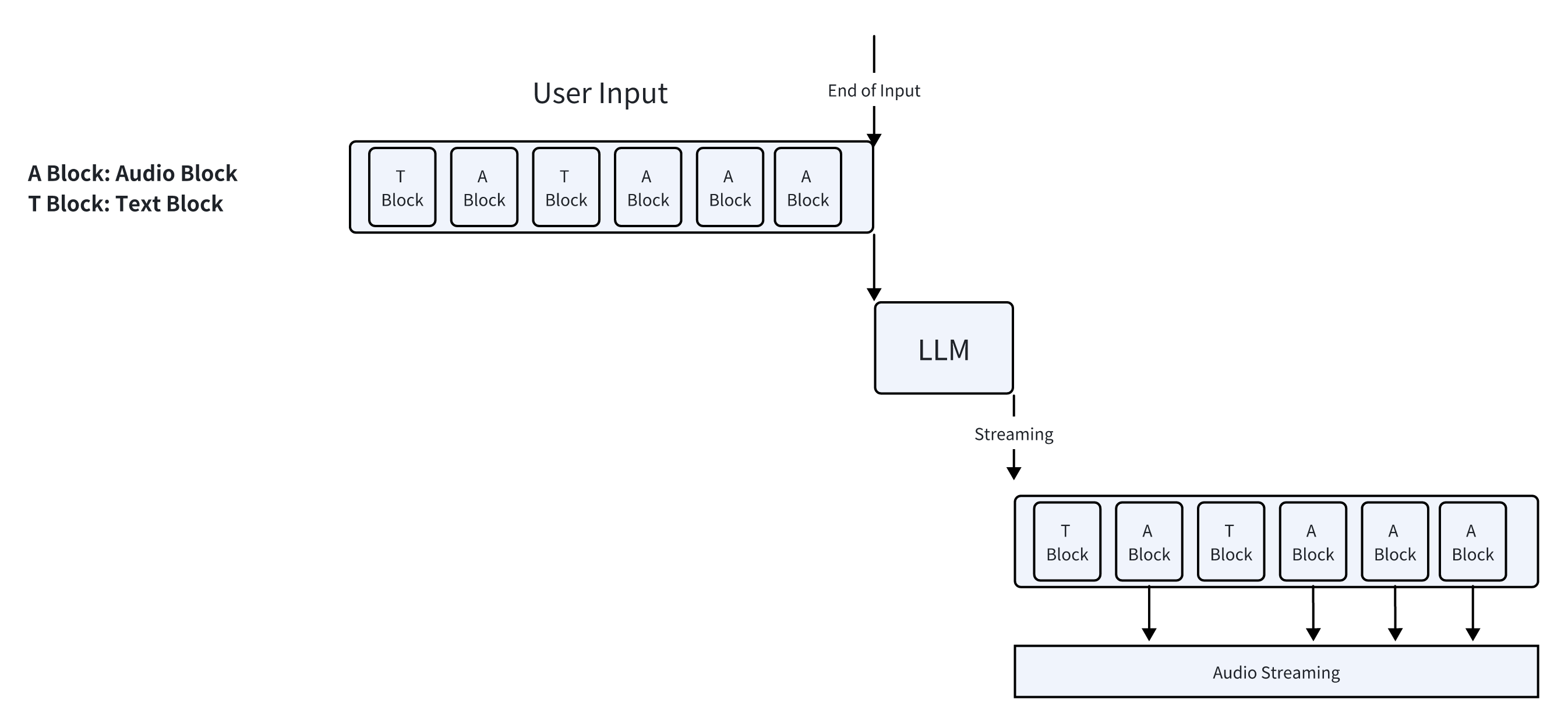

The first engineering issue encountered was latency. This implementation is the simplest, but it resulted in delays of over ten seconds. Even in the Windows XP era, such latency would have made users terminate the process. However, it’s obvious that the implementation can still be improved, so I continued to patch and modify it, akin to the first version of the tokenizer in Andrej’s tutorial.

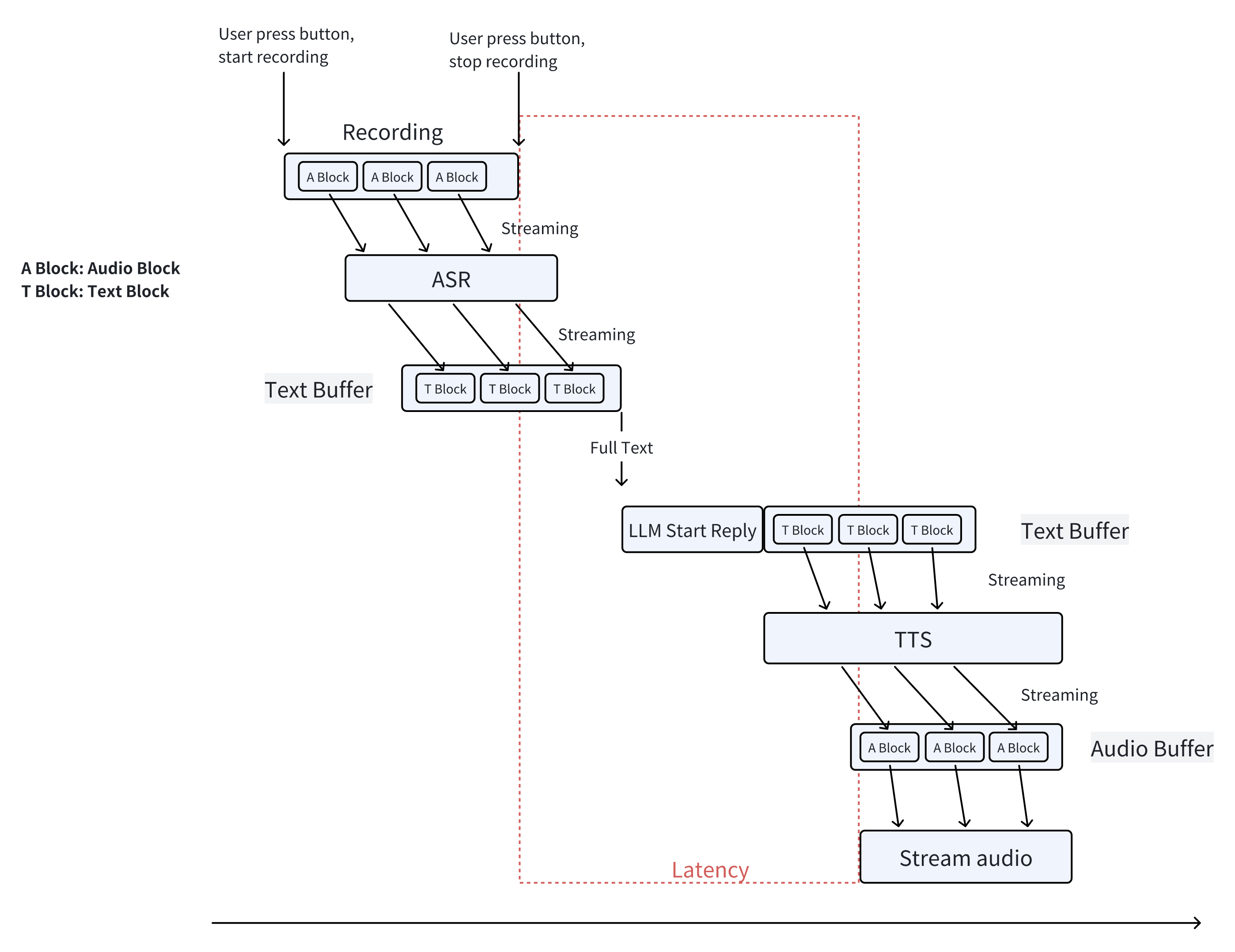

After a lot Make Do and Mend, the final implementation is shown above. All parts that could be streamlined were made to do so. Then the latency perceived by users, from the end of speaking to the start of playback of the first audio block, could be reduced to about 2-4 seconds. Latency could be further reduced by replacing the LLM with a fine-tuned smaller model.

Let’s stop at the engineering details and consider the significance of this example in terms of AI’s first principles. I’ll take a slight detour, but it’s worth it.

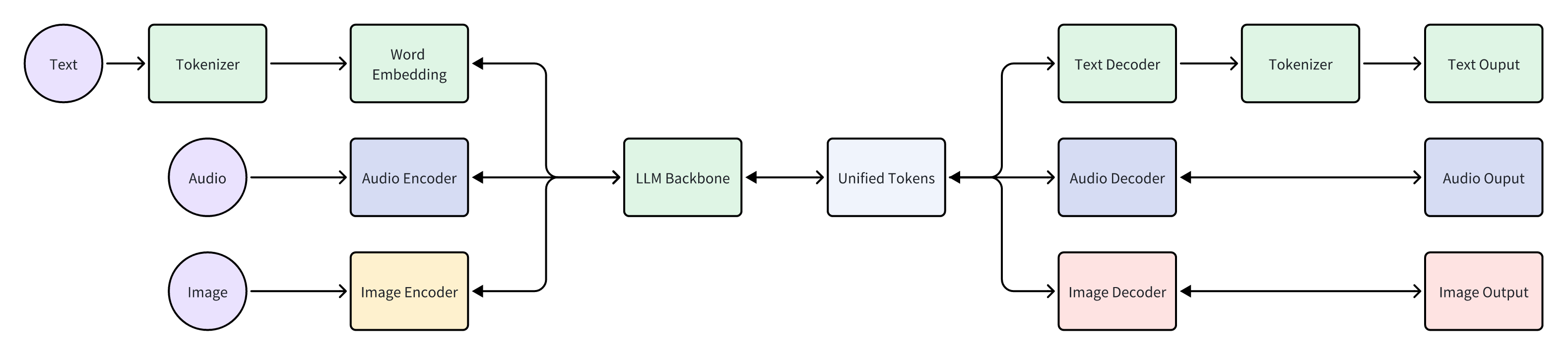

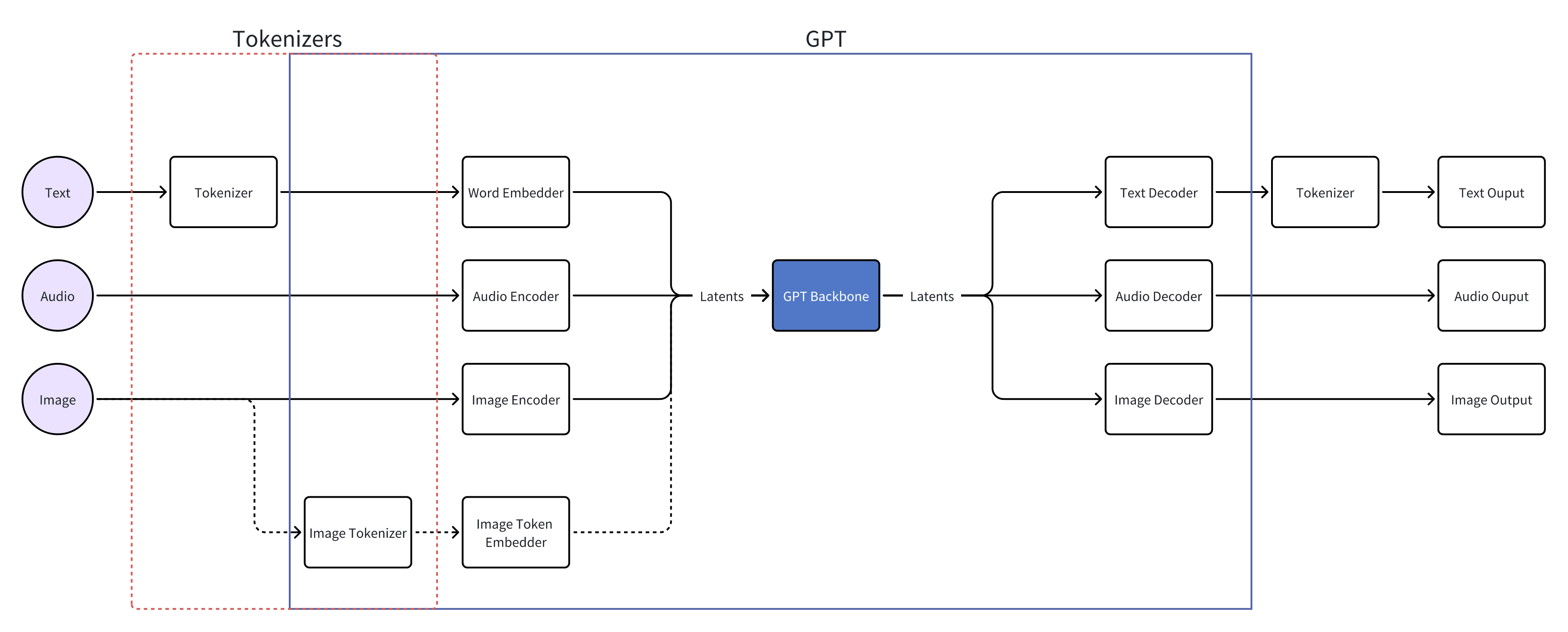

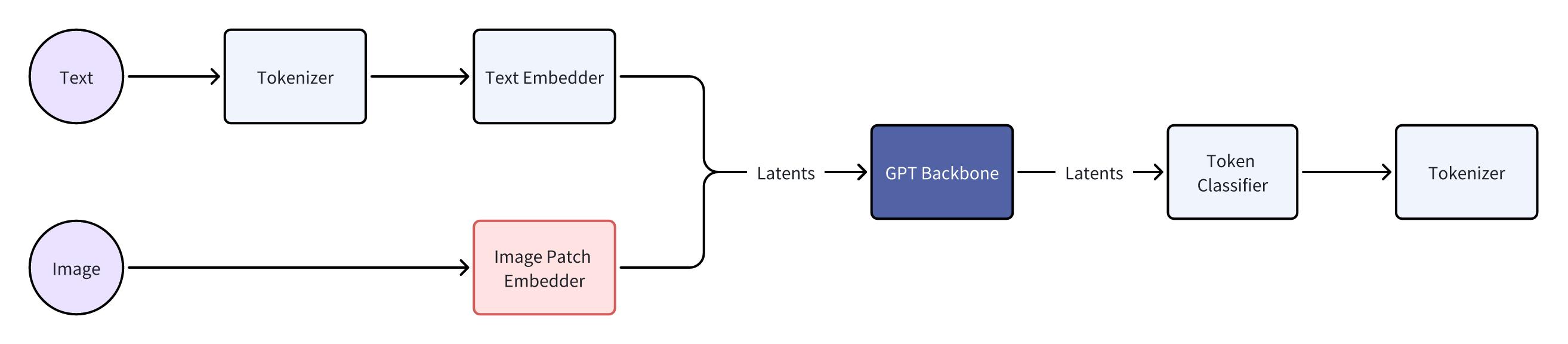

The detour is to consider the “blocks” concept in the final implementation, such as “audio blocks”, “text blocks”, and “speech blocks”. Recall what tokens are; they’re also “blocks”, chunks of strings. LLM’s input is in blocks of tokens, and its output is also blocks. Since everything is in blocks, can we unify “audio blocks”, “text blocks”, “speech blocks” and “tokens”, inputting these unified blocks into LLM, which can then output these blocks as well? In English literature, these are all called “tokens”; perhaps researchers were just too lazy to come up with new names. An example is Qwen-Audio. DL practitioners should check out its implementation. Although Qwen-Audio can accept text blocks and audio blocks, it can only output text blocks, i.e., tokens.

Side Note: GPT-4 Vision cuts images into patches, then embeds these image patches before feeding them into the model backbone.

But what’s the key difference between my final implementation and the unified block approach? The key difference lies in data representation and model design. Looking at the final implementation of this voice conversation system, it includes three parts and their respective heuristics:

| Component | Heuristics |

|---|---|

| ASR | ASR model training data, ASR model tokenizer, ASR model inference settings (e.g., hot words), etc. |

| LLM | As discussed earlier, tokenizer, corpus, and various inference settings. |

| TTS | TTS model training data, TTS model tokenizer, TTS inference settings (e.g., voice, speed), etc. |

In this system, the data interface between components is represented as text. ASR provides text to LLM, and LLM passes text to TTS. Not mentioning other heuristics, just the tokenizer alone, this system has three different ones.

One tokenizer is on the ASR output side, one on both the LLM input and output, and another on the TTS input.

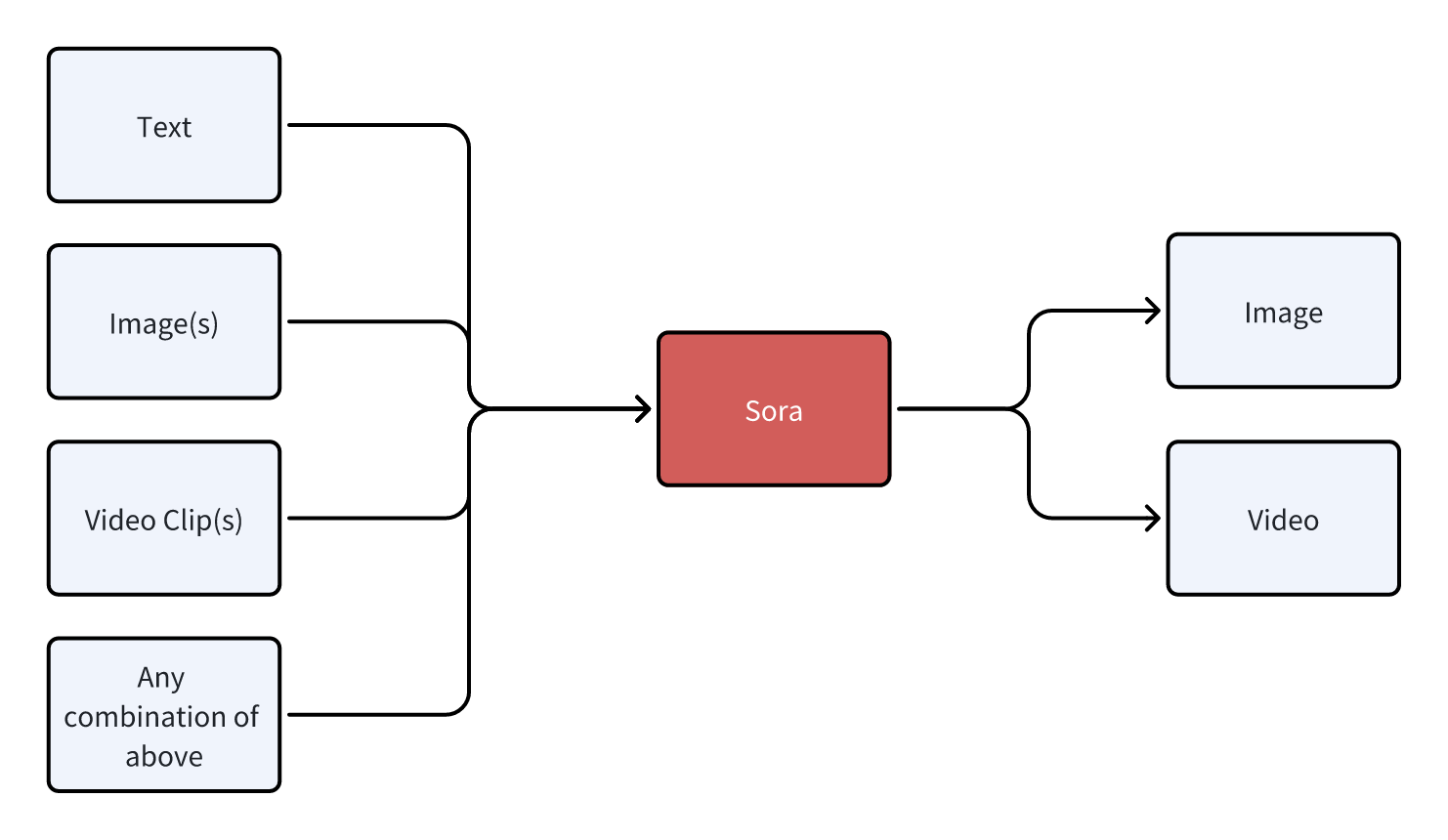

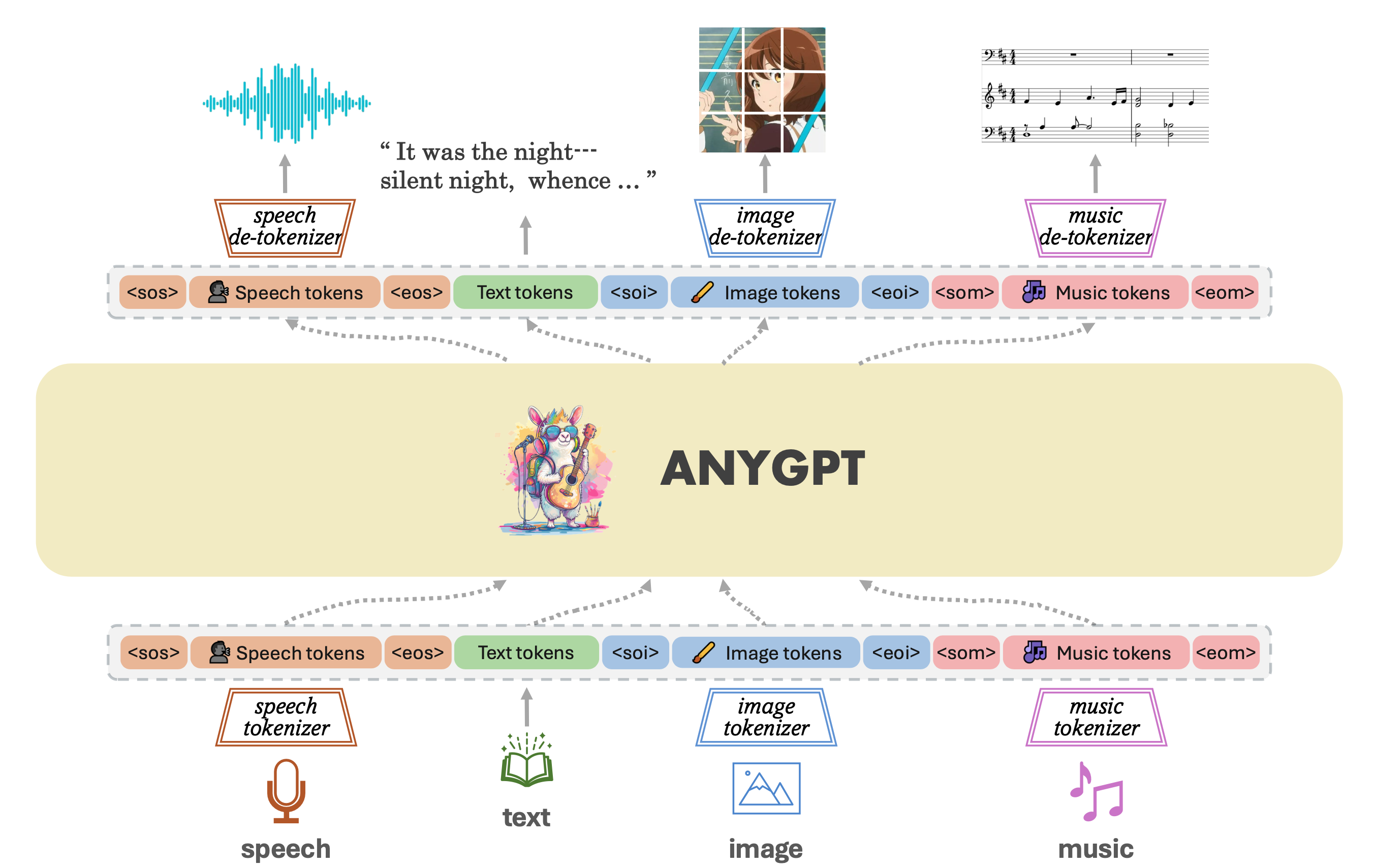

From the first example, it’s not hard to conclude that tokenizers cause information loss. For example, when a tokenizer directly replaces a “rare” token with “ Even if we managed to train a universal ASR and TTS capable of recognizing and producing various sounds, the system’s inter-communicative data representation being text would still incur unnecessary information loss. A straightforward example is myself, who as a Southerner has never seen snow. Although physics books describe snow’s structure and literature is filled with descriptions and poems about snow, none of these compare to going to the North and seeing snow with my own eyes, holding a handful of it. Many things, concepts, feelings, and nuances cannot be conveyed through text. I’ve got distracted a bit, but another real-world example is image understanding. After the release of GPT-3.5 and before GPT-4, many researchers wanted GPT-3.5 to “understand” images. One real approach was to use various CV models (such as object detection, semantic segmentation, instance segmentation) to extract as much information from images as possible. The information includes but is not limited to: However, after the release of GPT-4, people realized it could do much much more than the above, such as predicting whether a goal will be scored based on a shot photo, analyzing the micro-expressions and emotions of people in the image, etc. The value GPT-4 can create for users is undoubtedly much greater. And the (ASR + LLM) part of our LLM voice conversation system is strikingly similar to the (CV model + GPT-3.5) combination. Using DL terminology, both combinations are not end-to-end. Fans of Jujutsu Kaisen can imagine what it would be like if Kokichi Muta’s way of controlling machinery wasn’t through a direct connection with his talent but through sending messages 😂 Mechamaru: Boss, I heard a sound at 11 o’clock, very subtle, like a cat’s footsteps. Kokichi Muta: Alright, go check it out. If it’s a cat, pet it gently; if not, be careful of ambushes! Mechamaru: Boss, it’s a cat! Looks like a female cat, its fur is shiny, as if it used Rejoice! Kokichi Muta: Ohw~ How cute! Imagine if an LLM could directly understand text and audio, our voice conversation system’s architecture could be significantly simplified. Combining GPT-4 Vision’s visual capabilities, we can slightly expand the LLM architecture, resulting in a multimodal model like the following: The light green parts are the components all current LLMs have; the light blue parts are the ones needed to understand and generate audio; the light yellow parts is for GPT-4 Vision to understand images; and the light red parts are needed for the large model to generate images. If you’ve been closely following LLMs, this architecture should be very familiar. This is also the consensus in academia and industry for developing multimodal large models, which is to retain the LLM backbone while continuously adding encoders and decoders for various modalities, allowing the model to understand and generate data of various modalities. A recent example is Google’s Gemini, which includes encoders and decoders for audio, video, and images. Note that the encoders and decoders here are entirely different with those in traditional multimedia processing in terms of implementation. Here, the encoders and decoders are neural networks, where encoders encode data into embedding vectors, and decoders convert vectors back into data. So, what’s the implication of this example? I’ll leave that for you readers to conclude. Now, you can take a break, have a coffee, take a shower, even sleep or whatever. Just let that sink in. Because next, we’re entering a bonus chapter, an exciting question— The answer to this question can be simplistic—“Whatever capabilities AGI needs, OpenAI will implement”. However, this answer isn’t very instructive, but we can gradually break it down into finer-grained questions, such as: Let’s start with an example to get warmed up, then use another example to broaden our horizon. The first example is a question, “What’s next for Sora?” I believe the next step should be integrating the model’s components, training methods, and data into GPT. As mentioned earlier, GPT-4 can now see and understand image but cannot create. Creation is a capability of human, which AGI should also have. As for “Sora being a world simulator” or building a world model through Sora, that’s just a small part of the AGI blueprint, a means rather than an end. OpenAI’s vision is one and only: realizing AGI. OpenAI’s Vision aside, but what does Sora’s next step have to do with AI’s first principles? Let’s analyze based on input and output supported by Sora. Its input and output modalities are asymmetrical, but why is that a problem? It’s an issue of information flow, specifically communication. No doubt Sora is impressive, but I don’t think it’s reached the point of revolutionizing the film industry, as some claim. I work in AIGC for the film industry, and based on my interviews and observations, a significant portion of creators’ efforts is spent on communication and collaboration. For example, directors not only need to provide textual storyboards but also visual storyboards, and sometimes even make a video to demonstrate their intention, all to ensure the photographers accurately understands and executes the director’s ideas. When deviations occur during execution, the team needs to communicate continuously to resolve issues. However, Sora currently lacks the ability to communicate; creators can only hope their provided information is accurately understood by Sora, which then generates images or videos. Imagine you’re a director using Sora to shoot a film. Sora’s first version of the video, with created scenes and characters, is already stunning, but you feel the camera trajectory or position needs adjustment. How do you communicate this to Sora? It’s impossible. Perhaps you’ve also heard demands for “precise control”, but if we dig deeper, this is a communication problem, about whether users can continuously communicate with AI to solve challenges. And if we take another step towards AI’s first principles, the communication issue is a matter of information flow. To thoroughly solve the issues of communication and information flow, Sora cannot merely make incremental improvements (e.g., adding ControlNet, supporting LoRA, etc.). Instead, it needs to be integrated into a more general system, i.e., GPT. Imagine when GPT can communicate with you like an artist, photographer, or director. During the conversation, it can fully understand the text, music, videos, and images you give, and continuously modify its creations (images, videos, sounds, etc.) based on the communication. Only then will the film industry be revolutionized. The film and television industry is nothing without its people and communication! OpenAI will implement multimodal creative abilities for GPT, but just as Sony, as a camera manufacturer, doesn’t concern itself with what types of movies users shoot, OpenAI won’t care about the content users create with GPT (unless it’s for training purposes). This is also what Sam Altman meant by “Start businesses assuming AGI exists” in his YC-2024 talk. When we view the current AI unicorns through the lens of AI’s first principles and “Start businesses assuming AGI exists”, there’s one I think is worth discussing. This brings us to the second example—Elevenlabs. Elevenlabs’ technology (which they call Generative Voice AI) focuses mainly on voice, including TTS and speech-to-speech (S2S). TTS needs no further explanation, while S2S functionalities include: I’ve used Elevenlabs’ TTS. The quality of the generated audio is indeed much better than other competitors. However, I believe they will unfortunately become another victim of OpenAI’s AGI vision. Whether from the perspective of AI’s first principles or the principle “Whatever capabilities AGI needs, OpenAI will implement”, GPT will eventually gain the ability to understand and create audio. TTS and S2S are just a subset of the ability to understand and create audio. By then, we might even ask GPT to interpret what our dogs are saying and imagine an appropriate voice for them to greet us in various languages. Where will Elevenlabs’ moat be then? Through these two examples and the analysis based on AI’s first principles, I believe many people will have a more tangible feeling of the question, “Where does OpenAI draw the line?” Will traditional TTS and ASR inevitably become obsolete? When I first finished writing this section, I was confident the answer was affirmative. However, after carefully revisiting the LLM Voice Conversation Example, I believe traditional TTS and ASR manufacturers can survive by focusing on extremely niche scenarios. Historically, there are examples of this, such as traditional CV. Theoretically, if GPT-4-Vision is intelligent enough, traditional CV use cases (e.g., object detection, facial recognition) would all be crushed, but we haven’t reached the point of revolution yet, precisely because traditional CV has done enough optimizations for niche scenarios. So, what are the optimizations for niche scenarios for traditional TTS and ASR? After discussing with a colleague and friend, my conclusion is that they will ultimately move towards ultimate localization and customization. However, the consequence is that making money becomes much harder, and it’s mostly pittance for sweat. For example, suppose GPT-5 can understand and generate all kinds of sounds, then theoretically, TTS and ASR are entirely meaningless. But what about practical issues when landing it on applications, such as whether GPT-5 can recognize dialects or speak them? It’s very likely not, but these are the issues that practical implementation must address. Even if GPT-5 is smart enough to quickly learn through in-context learning, is its inference speed fast enough? This is also a key issue. Only extreme niche optimization can solve these practical issues. For fans of “Jujutsu Kaisen”: Would Kokichi Muta use TTS to communicate with Mechamaru? 😂 The examples mentioned are all manifestations of AI’s first principles. To ensure the efficient and complete flow of information within the system, we aim to embed as many capabilities as possible directly into the model, rather than dispersing them across various components. This design aims to minimize heuristics, allowing the model to learn from data, preserving as much useful information as possible. But how do we know what capabilities to embed into the model? In other words, what functions do we want the model to perform? What needs do we want it to meet? This leads us to product design. Even without considering the above questions, the development and training process of AI models is very similar to product development: When we view AI model development through the lens of product desigh thinking, we can gain a deeper understanding of AI technology. Just as product development needs precise positioning and locating needs, so does AI model development; just as product development faces uncertainties, so does AI model development; just as product development ultimately needs user validation, so does AI model evaluation. When we decide on the model’s capability scope in product design and embed these capabilities directly into the model through engineering, training, and iteration until they become part of the model, the model becomes a product. OpenAI’s 2023 DevDay presentation was very enlightening, showing the extensive product research behind LLMs. The presentation was titled Research × Product. Here, I’ll only highlight one example. It’s a simple yet complex question—“When a user says ‘hello,’ how should LLM respond?” You can probably think of hundreds of responses, but what makes them different? Which ones would be better? And what defines “better”? If you frequently use ChatGPT, the answer that first comes to mind probably is similar to: Hello! How can I assist you today? This response might seem bland, but upon closer inspection, it precisely positions GPT as an “assistant.” If replaced with something like “Hello! How’s your day going?” then GPT’s role shifts from an assistant to more of a friend. In fact, this impact is more profound than many might realize. When I tried to make GPT talk more like a friend through prompts, I had to write similar meanings three times in the prompt: “You’re not the user’s assistant but a friend”, “Don’t say like ‘how can I help you’”, “You and the user are equals, not subordinate. You don’t need to help them, and they don’t need your help.” ChatGPT’s assistant role deeply influences its responses and thought processes. I even think OpenAI could use “How can I assist you today” as ChatGPT’s product slogan and trademark it. We also see the model-as-product model emerging elsewhere. A prominent example is the various custom SD models and SD’s LoRA models. Many share the models they’ve trained on platforms like CivitAI or Liblib. Some are shared for free, while others require paid licenses. Users, as product managers for SD models, define the problem their models can solve, such as generating images in a specific aesthetic style or having certain image processing capabilities. Models can become products, and product needs can also drive model development, creating a product-driven AI model development cycle. An example is ControlNet. Originally, SD could only generate images guided by text, but actual needs demanded more, such as generating refined images based on sketches. This necessity inevitably forced model development. Another excellent example is Snapchat AI filters. This well-known example has been extensively analyzed, so I won’t elaborate further. Update (2024.10.09): Another great example is ChatGPT Canvas. In the announcement, OpenAI mentioned that to develop the core behaviors, like triggering the canvas, rewriting documents and making targeted edits, they used new data techniques, like “distilling outputs from OpenAI o1-preview”, to further finetune the GPT4o model. In other words, to enable Canvas, they not only implemented a lot of engineering code, but also heavily modified the GPT4o model itself! When a model’s capabilities can solve specific problems, the model becomes a product. Conversely, if existing model capabilities are insufficient to solve a particular problem, we can start from the need, develop a new model, and embed the capabilities into the model. If the problem is valuable enough or widespread enough, according to AI’s first principles, embedding capabilities directly into the model, instead of assembling and integrating existing AI components, can achieve a higher capability ceiling and create more value. Although not a hardware engineer, I love Apple’s slogan for recruiting hardware engineers - “The end the others see is our favorite start”. This deeply resonates with Alan Kay’s famous quote - “People who are really serious about software should make their own hardware.” In today’s AI era, I believe these quotes can evolve further: Developers serious about user experience should create their own AI models. Creating AI models is not for the sake of rebuilding wheels or following trends but a necessity to fundamentally improve user experience under AI’s first principles. Just as in the LLM Voice Conversation Example, after optimizing the code to its limits, I realized that further improvements in user experience are inseparable from advancements in the model itself. Such changes would undoubtedly involve another level of effort (and tears and sweat), but we might also discover opportunities that were unthinkable. The term “developers” here should not only refer to software developers but also hardware developers and designers for consumer electronics. But what does AI’s first principles mean for hardware product design? Although I’m neither a hardware engineer nor a designer, I’ll take an example and share my thoughts. Rabbit R1 has recently been a hot topic in the tech community with much controversy. Initially, based solely on its interactive features, my impression was somewhat negative. However, after reading their Research section, I believe they might be on a new path aligned with AI’s first principles. Since they’ve shared limited and somewhat vague technical details, my analysis is based on assumptions (italicized), meaning my views are only valid if these assumptions hold true. Rabbit R1’s primary interaction method is speech; users speak to it, and the AI analyzes the user’s intent to perform various actions. This is why the Rabbit team refers to their model as a Large Action Model - LAM. Suppose the voice module in LAM still uses ASR and TTS for implementation. In that case, similar to our analysis in the LLM Voice Conversation Example, it’s not difficult to conclude that the system’s capability upper bound won’t be very high. It would be at best a more intelligent and capable version of the Smartisan TNT. The issues Smartisan TNT faced with ASR, Rabbit R1 would face as well, such as difficulty recognizing speech in noisy environments. Smartisan TNT was ahead of its time in AI applications by 5 years, a case of being born at the wrong time. If you don’t know Smartisan TNT, I encourage you to check it out! It can only understand speeches but not other sounds, which means in terms of information volume, Rabbit R1 is basically the same as the mobile app of ChatGPT. When the model of ChatGPT app is updated to the next-gen that can understand sounds and countless sound-based use cases emerge, then Rabbit R1 becomes a new Nokia. By then, no one cares if Rabbit R1 is smaller than phones. As for output information volume, Rabbit R1 has speech output and a small display, which IMHO is not on par with phones. When it comes to input, both involve lifting a device; with a smartphone, you can take photos, type, and speak, but with the Rabbit R1, you’re limited to either taking photos or speaking. As for output, both the smartphone and the R1 can play audio, but the smartphone also excels at displaying text and images. Therefore, some criticisms of the Rabbit R1’s hardware are justified. I’ve always believed that smart glasses are the best platform for AI. With smart glasses, AI can see what you see and hear what you hear. You can also see and hear from AI, all without the need to lift a device. Is Rabbit’s product entirely without merit? I don’t think so, at least the Rabbit team’s ideas are ahead of most. In the Rabbit Research page introduction, they indeed train and fine-tune their model, integrating more and more capabilities into LAM itself, attempting to solve application problems at the model level. This direction aligns with AI’s first principles. As LAM acquires more capabilities, perhaps Rabbit R2 will be AI-empowered smart glasses? That would be revolutionary! ⚠️ This section requires some prerequisite knowledge, including a basic grasp of tokenizers, embeddings, and a solid understanding of backpropagation. If you don’t know these, you may skip this section. Alternatively, here are steps for getting started: In this LLM era, AI is more and more like human. Just as the development process of AI increasingly resembles the growth of us, AI’s IQ and EQ are becoming more human-like. Developing AI often feels like developing a product, blurring the line between technology and product. In fact, AI development is becoming more like educating a person. Many believe LLMs will take the core of future computing, with numerous components built around LLMs. Thus, LLMs become the kernel of an AI OS, with various components forming the AI OS peripheries and ecosystem. If we view AI OS as a team, then LLMs are the team’s key person; if we liken AI OS to a nervous system, then LLMs are the brain. Please remember these two analogies, as they can explain many Whys. AI OS is undoubtedly a platform, so let’s first put aside technical details and consider the roles within this platform. There are at least three different roles: In an OS, these three roles can interact with each other. For example, end users can directly use the OS’s capabilities or use applications; applications that developers provide need to call the OS’s capabilities and also serve end users. For instance, Rabbit also developed a Rabbit OS. In Rabbit OS, end users can use the OS’s capabilities and also use the Teach Mode to add more capabilities to the OS, making the interaction bidirectional. However, Rabbit OS can currently call existing applications’ capabilities, but existing applications can’t call Rabbit OS’s capabilities. Thus, based on our analysis, Rabbit OS cannot yet be considered an OS. This analysis is from the perspective of platform’s roles, but technically, what would AI OS’s APIs look like? Looking back at history, current APIs mainly come in two forms: text and binary formats. For example, when you call a library in your code, the API is in binary form; when you send and receive messages in JSON format, the API is based on text; when we write documentation or send messages to others, you can also consider human-to-human APIs as textual. However, we’re now extending LLM’s capabilities based on text. That seems very intuitive and natural. For instance: If you still remember AI’s first principles (and I hope you do) and the LLM voice conversation example, you might start to feel something is off. But if you’ve forgotten, let me give you another example. One of the analogies we used was comparing LLM to the core leader of a team. If you were in that position, have you ever encountered communication problems or misunderstandings with others? Sometimes feeling like your words don’t fully convey? Or feeling like your language has been misinterpreted? Have you ever wished, “If only they could directly understand my mind”? The other analogy compared LLM to the brain, think about it, does our brain communicate with other body components using text? For example, does the brain send a message to the fingers saying, “Press that button”? 🐶 Just as text is not the signal of our brain, LLM’s API is not based on text or binary numbers. When we view the LLM voice conversation example in the context of AI OS, LLM is the kernel of AI OS, while ASR and TTS are peripheries. However, in this application, the bottleneck of information is text. Based on text, AI OS’s API is the most limited heuristics we impose on AI OS. To unleash AI OS’s capabilities, we must remove this limitation, allowing LLM to interact with peripheries in a way it understands best and retains the most information. What is this method? Or, to put it another way, is there a third format of API? Those deeply familiar with DL might have already guessed. Yes, it’s embeddings. To be precise, it should be latent vectors (Latents). The “latent” here means “not understandable by humans.” But let’s not jump into conclusion but further destruct GPT, a type of LLM. As an LLM system, it typically includes four components: tokenizer, embedder, backbone network, and classifier/decoder. As a DL model, GPT only contains three parts: embedder/encoder, backbone network, and classifier/decoder. GPT can process images through an image encoder/embedder or use a special image tokenizer. This architecture is also the mainstream in academia and industry for developing multimodal models, with two advanced examples being Google Gemini and AnyGPT The GPT backbone network contains over 90% of the parameters, making it the main source of LLM’s IQ and EQ. Examining closely, the input and output of the GPT backbone network are embeddings/latent vectors, so latent vectors are truly LLM’s language, the signals the brain’s central system receives and emits. Latent vectors are the third form of API for AI OS, which I call ALI (Application Latent Interface). Text-based APIs are primarily for humans, designed to make software interactions understandable; binary APIs are mainly for traditional programs, designed for easy message parsing and passing by programs; and latent vector APIs, or ALIs, are for LLMs, ensuring information is efficiently and faithfully conveyed to AI. But this is not enough; AI OS needs in total three new types of APIs: These three types of APIs are not technically new; researchers have been using latent vectors, gradients, and tokenizers for a long time. However, researchers have not considered these elements at the API level, focusing more on model training and treating them as training techniques for different models. As mentioned earlier, models are products, extending to the idea that LLM’s APIs are also worth considering and designing from the perspectives of products, users, and ecosystems. Next, I will provide several examples to further explain the key questions of these three new APIs, namely “What”, “Why”, and “How”. Let’s first view GPT from another perspective: We take GPT as a pipeline, with the backbone network as the divider. Components that feed information to the backbone network are upstream, while components that receive information from the backbone network are downstream. Whether upstream or downstream, these components can be learning-based models, such as neural networks, or non-learning programs, such as tokenizers. Review: Why isn’t a tokenizer considered a learning model? See the section on The Significance of AI’s First Principles for System Design. The Latent Vector API allows us to bypass the tokenizer, directly passing latent vectors to the LLM backbone, and the LLM backbone can also directly pass latent vectors to downstream components. This API ensures information flows efficiently and faithfully within this pipeline, as it uses LLM’s own language. This is the most precise and strongest answer to “Why do we need a Latent Vector API?” Latent vectors have several applications in downstream components. We’ve seen three, such as: There are many more examples of downstream components. Essentially, you can design various learning models to convert the information in latent vectors into another form. A recent example is Stable Diffusion 3. SD3 uses the T5 model as a text encoder, and its diffusion module for generating images uses the latent vectors output by T5. The T5 model is a language model with 4.7 billion parameters, accounting for more than half of SD3’s total weights. Thus, we can consider SD3’s diffusion module as a downstream component of T5, capable of generating exquisite images based on T5’s latent vectors. When we limit GPT’s components to learnable components, we can start discussing the significance of the Gradient API. The Gradient API is mainly for training new upstream learnable components. Note that there are two keyword here: “upstream” and “learnable components.” The image above shows the forward pass of model training, while the image below depicts the backward pass of model training. If we want to train new downstream learning components, the gradient propagation and parameter update process during backpropagation will stop at the downstream learning components, so there’s no need for the LLM backbone network, i.e., the AI OS kernel, to provide a Gradient API; However, if we want to train a new upstream learning component, gradient propagation must pass through the AI OS kernel, necessitating a Gradient API by the AI OS. When the scale of the GPT backbone is still manageable, we can run DL training frameworks on our servers to perform backpropagation and train upstream components. At this point, gradient propagation hasn’t been elevated to the API level. An example is MiniGPT-4. My senior fellow used KAUST’s GPU servers to train an image embedder (more precisely, the embedder’s projection layer). For the GPT at the time (LLaMA 1 / Alpaca), this image embedder served as a new upstream component, enabling GPT to “see” images. When the scale of the GPT backbone exceeds what most people and organizations (including KAUST) can handle, we’ll need the LLM provider to help us compute gradients, specifically the part shown below. In fact, we can consider the network that computes gradients as another model. It has the same number of parameters as the original GPT but performs entirely different computations. It accepts gradients (of latent vectors) as input and outputs gradients. With the Latent Vector API and Gradient API, we, as developers of AI OS, can develop/train components upstream of the AI OS core to expand capabilities, and also develop/train components downstream of the AI OS kernel to expand capabilities. From the perspective of a DL system, all learnable components dependent on the AI OS core will have representations aligned with the LLM’s one. A unified representation is a powerful language. Recall the example of CLIP; without CLIP or similar research, it would have been difficult for text and image representations to align, making the big bang of SD and various text-to-image models impossible. The Latent Vector API and Gradient API enable one same language among AI modules. These AI modules can be small perceptrons or LLMs with latent vector translation layers (projection layers)! At this point, AI modules have “neural links,” similar to the creatures on Pandora! Then they can build the Babel Tower of AGI together. The Latent Vector API combined with the Gradient API enables many interesting explorations. One of them is Gist Tokens. Taking text as an example, prompt tokens are tokenized by the tokenizer and converted into corresponding latent vectors by a giant lookup table. Thus, what the LLM backbone sees is a sequence of latent vectors corresponding to the prompt tokens. If the prompt is too long, it occupies valuable context window space. However, by training Gist Tokens, we can compress the information of a long sequence of latent vectors of prompt tokens into a few latent vectors. “Gist Token” isn’t quite the right name; it should be “Gist Latents”. The image above illustrates the training of Gist Tokens. During the forward pass, the latent vectors of prompt tokens form a sequence, followed by inserting N Gist Token latent vectors. Combined with attention masking, GPT predicts the answer while only seeing Gist Token latent vectors, not the prompt tokens. The training goal is for GPT’s predicted answer to be as close as possible to the answer without masking the prompt. Thus, we can say the Gist Latents contain information almost identical to the prompt’s. During backpropagation, due to attention masking, gradients do not propagate to the prompt token latent vectors but instead to the Gist Latents, optimizing them. This training process focuses on latent vectors and their gradients, while the tokenizer and word embeddings simply map the prompt to a sequence of latent vectors. If we view this process through the pipeline perspective, Gist Latents are upstream of the GPT backbone network, providing information to the AI OS kernel. In this example, with the Latent Vector API and Gradient API, we, as users of the AI OS kernel, can condense complex instructions, improving operational efficiency and reducing inference costs. Of course, don’t forget, we can still use the text API to expand capabilities upstream and downstream of LLM. For example, Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) enhances LLM’s capabilities by using a search engine upstream; Function Calling relies on LLM outputting formatted text to call downstream components, enhancing the entire AI OS system’s capabilities at the textual level. When we closely examine the components of AI OS, we find a bridging layer between human-understandable language (i.e., text) and LLM-understandable language (i.e., latent vectors). Language is the manifestation of thought. Text carries human thoughts and logic, while latent vectors contain LLM’s thoughts and logic. The bridging layer consists of the text tokenizer, token embedder, and token classifier. The above paragraph might seem abstract, but we actually have a very practical example—AnyGPT. Let’s review the (text) token embedder, which is essentially a large lookup table. It has as many rows as there are text tokens, whose length typically ranging from 5,000 to 1,000,000. For example: The vocabulary for text tokens is derived from the tokenizer’s iteration, but we can also manually add vocabulary. Reference: Figure 1 from the AnyGPT paper Looking at AnyGPT’s architecture, we notice the researchers added special tokens like When AnyGPT wants to generate an image, it first outputs a special latent vector recognized by the token classifier as Viewing AnyGPT’s architecture, it closely resembles our AI OS pipeline diagram, so you can try to categorize which components are upstream and which are downstream of the AnyGPT backbone network. After training our custom learnable components using the Latent Vector API and Gradient API, we need to know when to call these components. Just like AnyGPT added This is where the Tokenizer API comes into play. Our ultimate goal is to know when to call these components. Therefore, we need an API to add new vocabulary and train the corresponding latent vectors for new tokens, and that’s it. In Octopus V2, the authors proposed the concept of functional tokens, which is actually a specialization of the tokenizer API. Interestingly, the time they uploaded the paper was one month later than when I finished this section. If you have enough imagination and creativity, these three APIs are enough to turn the world around. For example, we could convert data from force sensors through an encoder into latent vectors recognizable by LLM, giving LLM a sense of touch; train a latent vector to motor movement decoder, allowing LLM to control its own body. Even in the future, when brain-computer interfaces mature, we could train a brainwave encoder to transmit our brainwaves to LLM; and use a brainwave decoder to translate LLM’s latent vectors into electrical currents for human neural synapses. By then, we could communicate bidirectionally with AGI through mere thought! Doesn’t this resemble the technology in “The Matrix”? Starting from a character in “Jujutsu Kaisen”—Kokichi Muta, we’ve discussed what AI’s first principles are, extending to their significance for system design and broader product design, interspersed with several examples and side sections. Let’s summarize the highlights and key points: Thank you for reading this far! To write this article, I started brainstorming from the first day of the Chinese New Year, and after writing intermittently, a month has passed. This represents a year and a half of my thoughts on working with LLM and AIGC models and applications. I also want to thank two friends, one who offered me an opportunity to think about the future direction of AI in practice, and another who provided many insights through continuous discussions. In fact, the inspiration for the Tokenizer API came from the second friend. My contribution was generalizing this concept to the API level and discussing it in the context of AI OS. On a broader level, I firmly believe this wave of AI, started from LLMs, can profoundly change our society for the better. At the very least, I hope everyone can access the knowledge they seek through LLMs. I believe knowledge should be affordable for everyone. If you’re interested in using LLMs to bridge the knowledge gap, feel free to come and chat. Perhaps we can do something different together :) I was pleasantly shocked today at the MiniMax Link Day. Junjie Yan, the CEO and founder of MiniMax, shared how their technology and users mutually benefit each other. User feedback promotes the growth of the model. However, globally, less than 5% of people are users. He then talked about their determination to tackle the challenges to develop linear attention mechanisms, stating: “If the capability remains unchanged, faster models can be used by more people; and the more people use the model, the better it becomes. In this sense, ‘fast’ means ‘good’.” During the subsequent forum, founders from various tech fields resonated on a point: technology is important, but the organizational structure of a company is equally crucial. New technologies require new organizational forms. This made me start thinking that perhaps the first principles of AI need to be discussed on a bigger picture. For instance, AI models and data themselves should follow the aforementioned first principles, but the pipelines for models and data also have their own first principles. Teams and companies developing models should be designed around these principles. The term “information volume” in the context of data collection pipelines might refer to the quality, quantity, and flow speed of user feedback information. For teams, the capabilities built around “information volume” might involve exceptional user operation abilities and iteration capabilities. Besides, I can’t help but marvel that the release of effective linear attention, which performs on par with the conventional attention mechanisms, at the Link Day could be a seemingly ordinary but very significant turning point in human technology. Soon, we might have billions of tokens of effective contexts, and at that time, science and civilization will usher in a new explosive era with the help of AI. 💥 Version: 0.3.0 Date: 2024-02-19 License: CC BY-SA 4.0 2024.03.14: Finished first translation rectification. 2024.03.18: Update a bit of wording 2024.05.09: Add reference to Octopus V2 2024.08.31: Add the updates on MiniMax Link Day 2024.10.09: Add the update about ChatGPT Canvas

> Where Does OpenAI Draw the Line?

The Significance of AI’s First Principles for Product Design

> Hello! How can I assist you today™

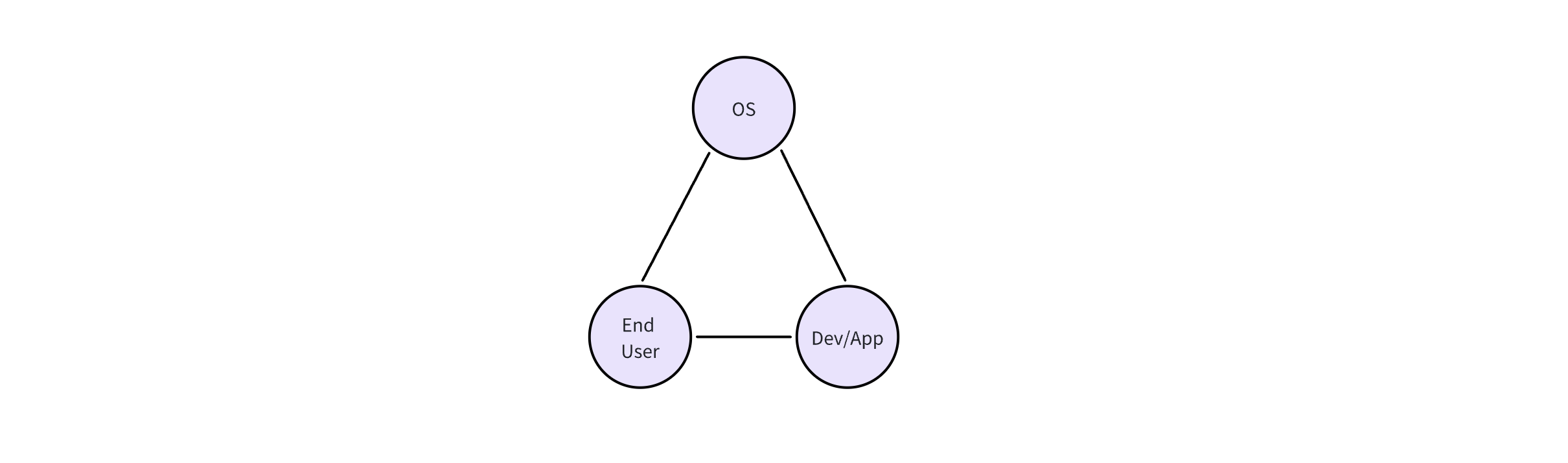

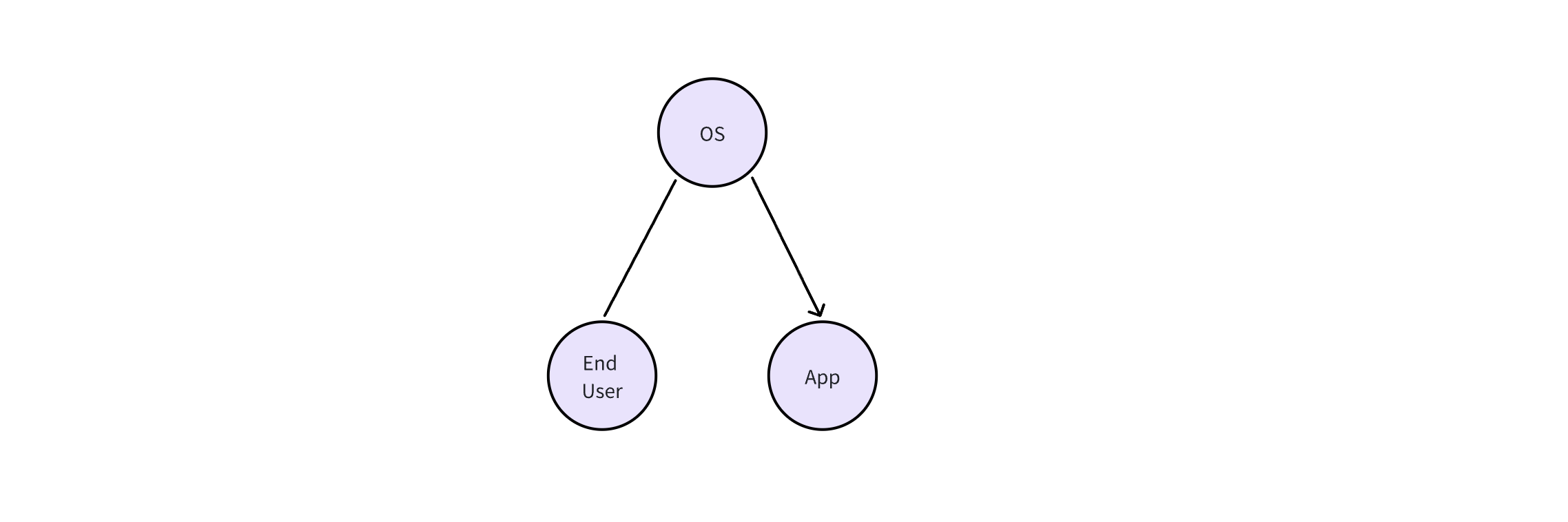

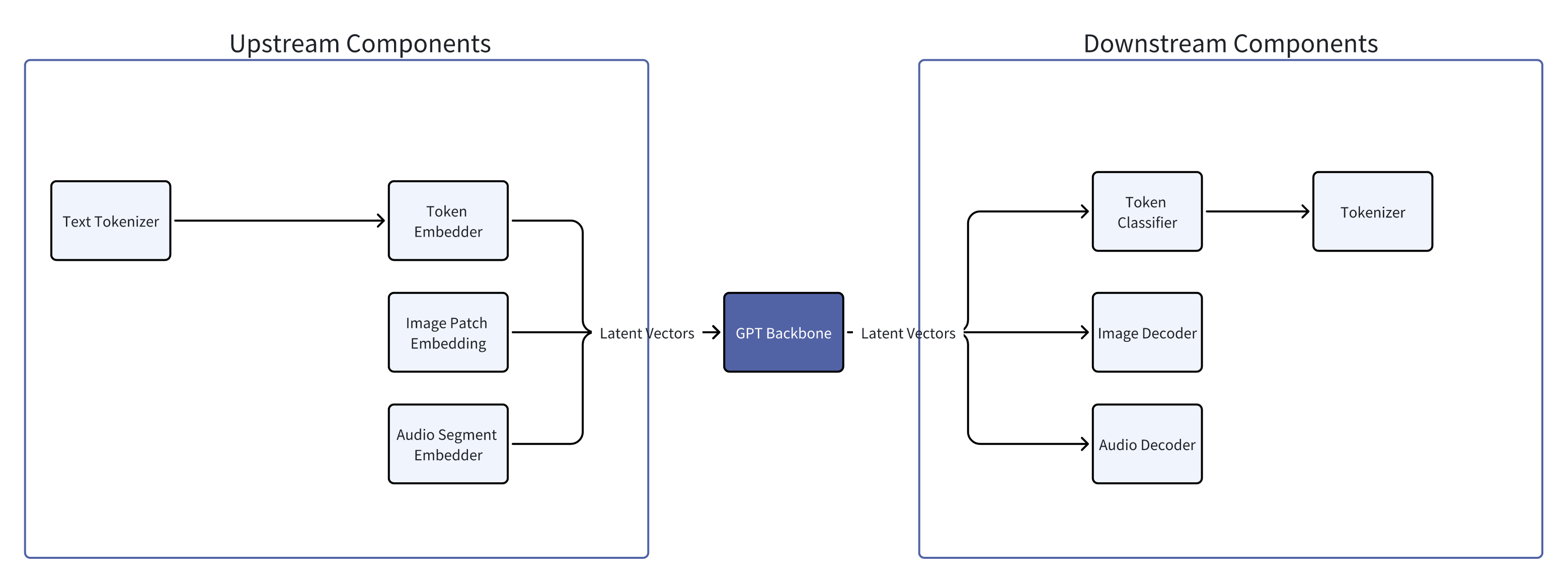

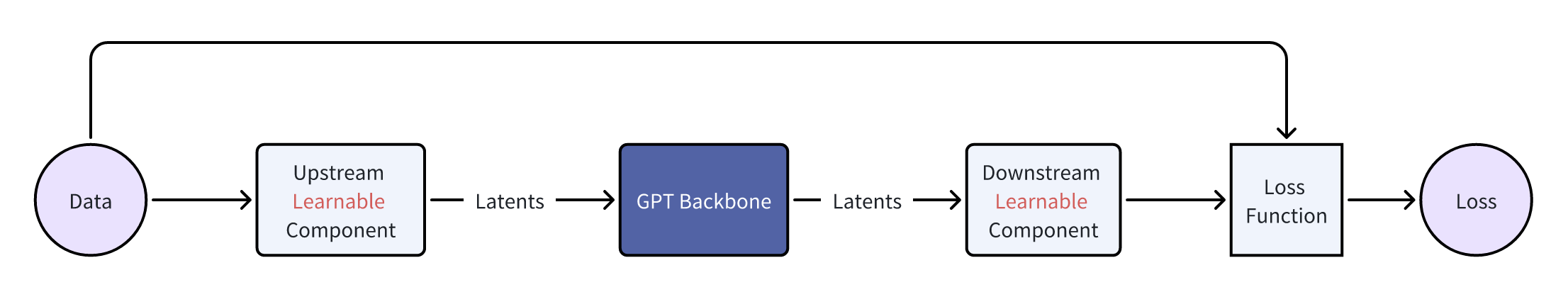

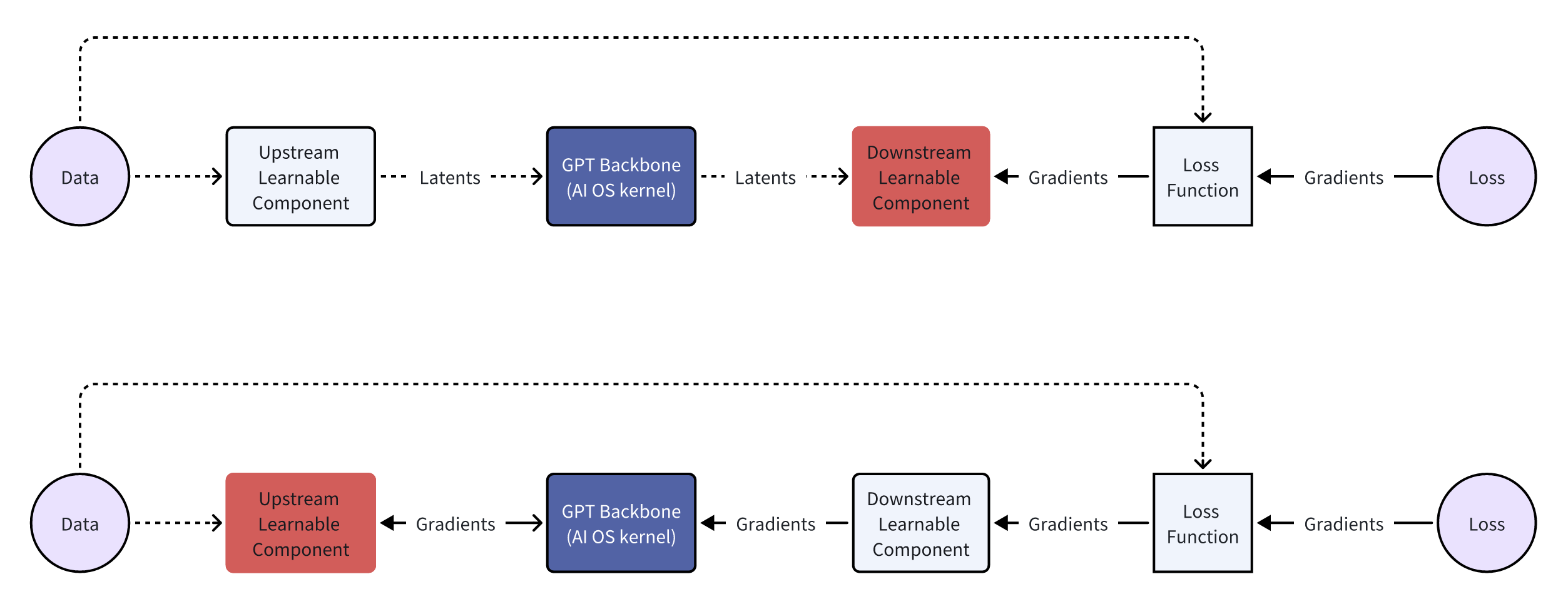

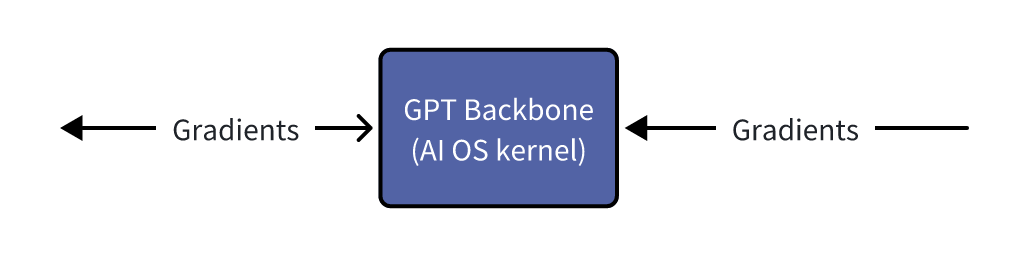

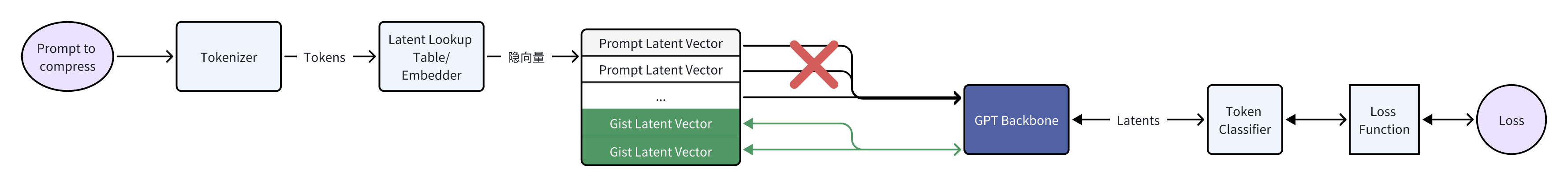

> AI OS

ID Token Latent Vector 0 a [0.1, 0.2, …] 1 b [0.2, 0.5, …] … … … 999999 he [0.3, 0.1, …]

<sos>, <eos>, <soi>, and <eoi>. Those familiar with LLMs can probably guess the meanings of these special tokens:<sos> stands for “start of speech”<eos> stands for “end of speech”<soi> stands for “start of image”<eoi> stands for “end of image”<soi>. When the program detects <soi>, subsequent latent vectors are not passed to the token classifier but to the image decoder (referred to as the image detokenizer in the paper); when AnyGPT finishes generating image tokens, it outputs another special latent vector corresponding to <eoi>, signaling the program to stop passing latent vectors to the image decoder.<soi> and <eoi> to indicate when to start or stop calling the image decoder, for every custom component x, we need to add <sox> and <eox> to the vocabulary, token embedder (i.e., a lookup table), and train the corresponding latent vectors and token classifier. If you’re familiar with DL, these operations are simply adding two rows to two matrices and optimizing the parameters of these 4 (=2×2) rows.Summary and Highlights

Afterword

2024.08.31 Update: MiniMax Link Day

Metadata

Changelog