A Complete Guide to WASIp2 for Rust and Python Programmers

A guide to a true universal runtime

Since long time ago, programmers have dreamed of a universal runtime that unifies all the languages and platforms. Any programs targeting this runtime can be run on any platform without any modification. One (virtual) machine to run them all. For me, the first “universal runtime” that comes to mind is Java Virtual Machine (JVM). If you come from different backgrounds, you might think of .NET Runtime, Beam VM, or even Javascript runtimes. Yes, they are successful and widely used, but they are still not that universal. For example, JVM is primarily designed for Java, so a garbage collector is built in, but not all languages need it. My favorite Rust does not need it either, while my another favorite, Python, does garbage collection a bit differently from Java. As web browsers and web technologies are everywhere, how about just writing JS programs? That would be possible (take a look at Electron and Node.js), but we all know JS is a bit slow compared to compiled languages like C/C++/Rust. But the direction is roughly right, so we have a new and yet another solution: WebAssembly (WASM).

WASM is only part of the story of this blog. Here I am going to introduce WebAssembly System Interface Preview 2 (WASIp2). As the name suggests, WASIp2 is about the interface of WASM. In this guide, I will show you how to compile Rust and Python programs to WASIp2 components (special WASM modules), compose them into a more powerful component, and how to run these components in Rust, Python and Wasmtime (the standard WASM runtime). For the code in this guide, you can find the complete code in wasi_mindmap repository.

Copyrights and References

Before we start, first and foremost, I want to make it clear that this guide is the combination of official documents and my experiences when stumbling through the tutorials in the official documents and various GitHub issues. In contrast to the official documents, I want to make this guide self-contained from concepts to implementations but I don’t want make crappy summaries of some well-written documents, so I will just copy and paste some content from the official documents. When I copy and paste, I will end the very paragraphs with symbol ↪ to link the reference, avoiding excessive reading distraction. When I want to highlight some quotes, I will just use quote marks and quote sections.

Here are the references:

- Mostly from The WebAssembly Component Model documentation (hereafter “WACMDoc” for short), licensed under CC-BY-4.0.

- README and documentation of

wit-bindgen, licensed under Apache-2.0 and MIT.- Documentation of Wasmtime, licensed under Apache-2.0.

- Related GitHub issues: I will link them explicitly in-situ.

This guide is also licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 which is compatible with the licenses of the references.

WASM

Before we dive into WASIp2, let’s first take a look at WASM.

Quoting from Wikipedia:

WebAssembly (Wasm) defines a portable binary-code format and a corresponding text format for executable programs as well as software interfaces for facilitating communication between such programs and their host environment.

The main goal of WebAssembly is to facilitate high-performance applications on web pages, but it is also designed to be usable in non-web environments. It is an open standard intended to support any language on any operating system, and in practice many of the most popular languages already have at least some level of support.

The very last sentence in the quote block is the key for us. WASM does not only support languages like C/C++/Rust, but also supports languages like Python, JavaScript, etc. Programs can be compiled as WASM modules and run in any environment that supports WASM.

Just to summarize, the key points are:

- “Any language” can be compiled to WASM.

- WASM modules can be run in any environment that supports WASM.

If you are interested in various use cases of WASM and why WASM is getting momentum, WASM in the Wild series is a good starting point.

Concept: WASIp2

OK, now that we have “the one” virtual machine, is it the end of the story? Not quite.

For a simple program, it is often enough to just compile it as a WASM module and run it on a WASM runtime. By “simple”, I mean a program that can be written in a single language, say Rust, C or Python. But more complexity arises from a curious and practical question: Since these programs are compiled to a common assembly language as modules, can we compose them into a more powerful program?

If you come from compiled languages, you might know something about linking/linker and application binary interfaces (ABIs), which do roughly the same, except that the common assembly is something specific to processors, for example, x86 assembly.

To do the composition of WASM modules, we need to define a standard for the interfaces of WASM modules. This is where WASIp2 comes in.

WASM module + WASIp2 interface specs ≈ WASIp2 component

For brevity, in the following sections, I will just call:

- WASM module ⇒ module

- WASIp2 component ⇒ component

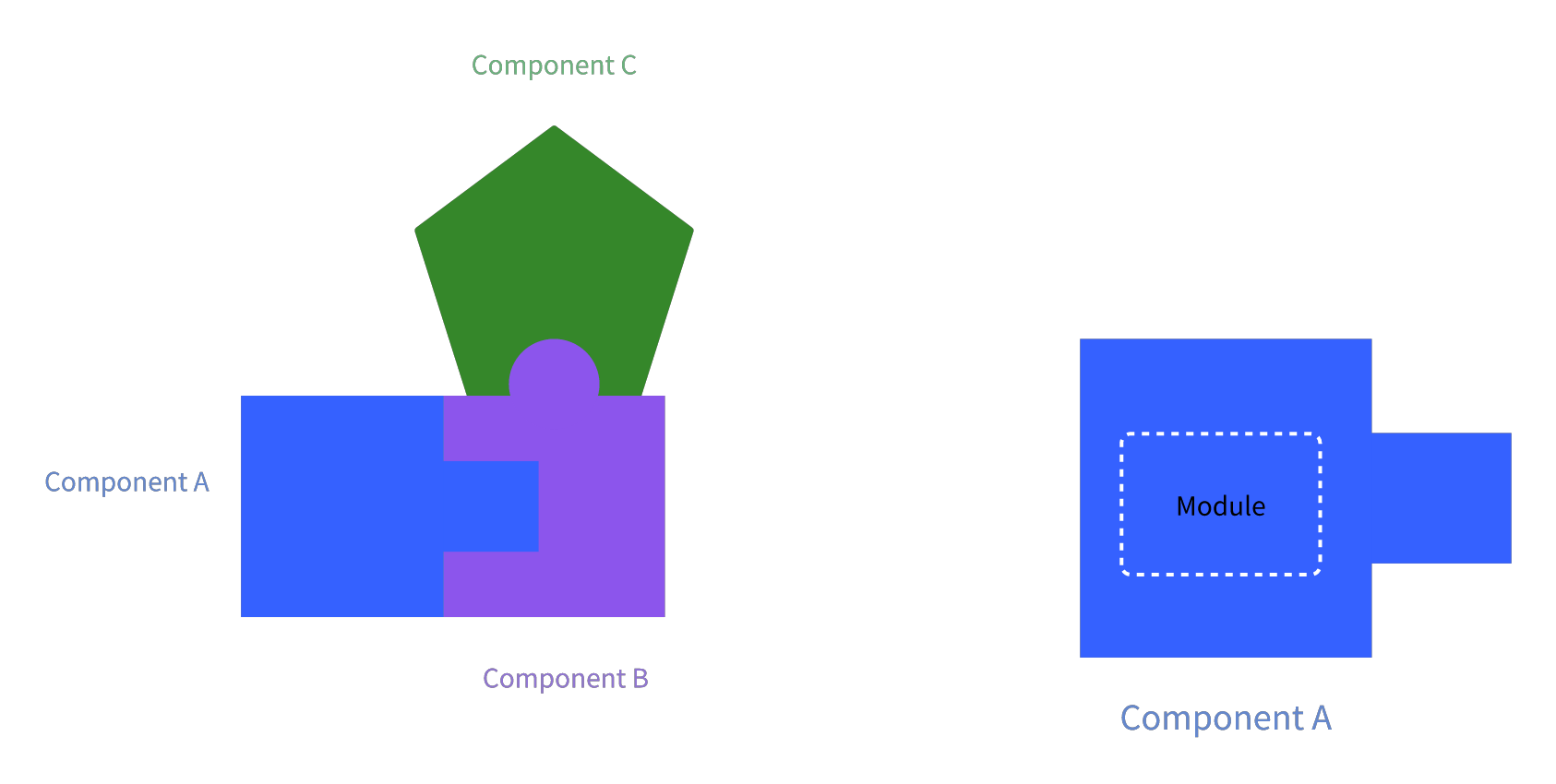

A visualized analogy is Lego blocks. Below we have three blocks (i.e., components) and each block has a different shape. Consider that the shape of a block/component is defined by its WASIp2 interface specs. The core logic of a component is still inside a module, though.

Component A has an export that is compatible with Component B’s import. Component C requires an import satisified by Component B’s export.

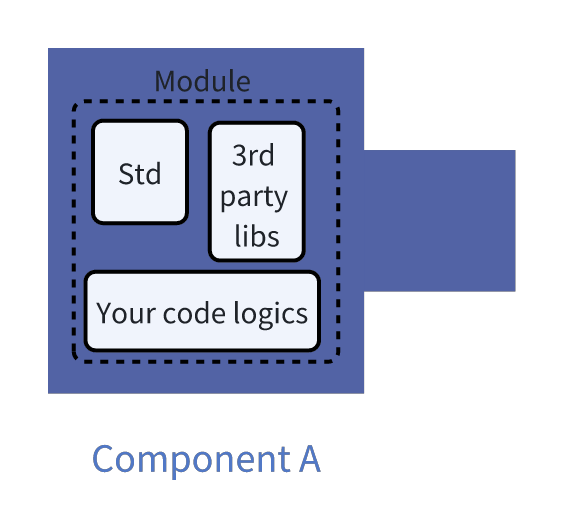

Zooming in, Component A has a module as its core.

Basics

There are 5 basic concepts in WASIp2: components, interfaces, worlds, WIT and packages.

Components, as we know, are building blocks. Logically, components are containers for modules or other components, which express their interfaces and dependencies via WIT. Conceptually, components are self-describing units of code that interact only through interfaces. “self-describing” means components have interface descriptions inside. Physically, a component is a specially-formatted WebAssembly file. Internally, the component could include multiple traditional (“core”) WebAssembly modules, and sub-components, composed via their imports and exports. So, for instance, the composed file of Component A, B and C is also a component. ↪

An interface describes a single-focus, composable contract, through which components can interact with each other and with hosts. Interfaces describe the types and functions used to carry out that interaction. ↪

A WIT world is a higher-level contract that describes a component’s capabilities and needs. On one hand, a world describes the shape of a component - it says which interfaces the component exposes for other code to call (its exports), and which interfaces the component depends on (its imports). A world only defines the surface of a component, not the internal behaviour. On the other hand though, a world defines a hosting environment for components. An environment supports a world by providing implementations for all of the imports and by optionally invoking one or more of the exports. ↪

The WIT (Wasm Interface Type) language is used to define interfaces and worlds. A WIT spec, or “WASIp2 interface specs” as we informally call earlier, is stored in a .wit file. For details of WIT language, please see the related section of WACMDoc.

A WIT package is a set of one or more WIT (Wasm Interface Type) files containing a related set of interfaces and worlds. ↪

OK, enough talking. Let’s take a look at the simplest example of WIT files:

// interfaced-adder.wit

package wasi-mindmap:interfaced-adder;

interface add {

add: func(a: s32, b: s32) -> s32;

}

world adder {

export add;

}

wasi-mindmap is the namespace for this package, interfaced-adder the name of this package. When we refer to a package, we usually refer it with its package ID, wasi-mindmap:interfaced-adder in our case. A package ID can optionally include a semver-compliant version, wasi-mindmap:interfaced-adder@0.0.1 for example.

In this package, we define a world adder for adder implementations. This world exports only one interface named add. The interface defines only one item, a function named add. Of course, in a world, we can import and export more interfaces. And an interface can define more items like data types, resources and/or functions.

Since this is just a tutorial, not a book, we won’t dig into the WIT specification, but later we will have a more complex WIT file and corresponding component, I promise.

More Code

For the purpose of demonstration, I will write programs in Python and Rust. These two are my favorite, so please bear with me. As WASM is “universal”, you can try to compile code in your favorite languages into components. This section of WACMDoc shows more examples in more languages.

Adder Components

When I previously said “the simplest example”, it’s partially correct and partially wrong. There is a simpler WIT file than interfaced-adder.wit. The name, of course, is adder.wit:

package wasi-mindmap:adder;

world adder {

export add: func(a: s32, b: s32) -> s32;

}

The adder world in adder.wit directly exports a function add rather than exposing it via interface add. This is technically allowed but also a bit unusual. We will come back to the reason when we talk about compositions. For now, we use adder.wit for demonstrating how an adder component can be implemented.

For Rust implementation, you need nothing more than the wasm-wasip2 target of rustc.

To install the

wasm-wasip2target, runrustup target add wasm32-wasip2

The cargo project is simple as below:

├── Cargo.toml

├── src

│ └── lib.rs

└── wit

└── adder.wit

The dependencies are minimum:

# Cargo.toml

[package]

name = "guest-adder-rs"

version = "0.1.0"

edition = "2021"

[lib]

crate-type = ["cdylib"]

[dependencies]

wit-bindgen = "0.46"

With the magical wit_bindgen::generate macro, we don’t have to write boilerplate glue code. Even better, all implementation code is statically checked by our beloved rustc.

// Use a procedural macro to generate bindings for the world we specified in

// `wit/adder.wit`

wit_bindgen::generate!({

// the name of the world in the `*.wit-files` input file

world: "adder",

});

// Define a custom type and implement the generated `Guest` trait for it which

// represents implementing all the necessary exported interfaces for this

// component.

struct Adder;

impl Guest for Adder {

fn add(a: i32, b: i32) -> i32 {

a + b

}

}

// export! defines that the `Adder` struct defined below is going to define

// the exports of the `world`

export!(Adder);

With dozens of lines in total, you can then simply run cargo build --target wasm32-wasip2 and get a freshly-baked component guest_adder_rs.wasm in target/wasm32-wasip2/debug.

To inspect

.wasmfiles and more, you can installwasm-toolsbycargo install --locked wasm-tools, or refer to the repo for more instructions.To see

guest_adder_rs.wasmcomponent is indeed self-describing:$ wasm-tools component wit guest_adder_rs.wasm package root:component; world root { export add: func(a: s32, b: s32) -> s32; }

guest_adder_rs.wasmitself includes all necessary descriptions of its import and export interfaces.

Adder in Python

Python doesn’t have native support for WASIp2, so we need to install componentize-py by

pip3 install componentize-py

For a Python program to implement the exports of world adder, we can generate bindings by:

componentize-py --wit-path adder.wit --world adder bindings ./adder

which will generate a Python package in the current directory named adder. Importing from adder Python package, your Python program gets a proper abstract class to inherit from.

# in guest-adder.py, place it in ./adder

# wit_world is generated in ./adder

from wit_world import WitWorld

# the class MUST be named `WitWorld`, same as the abstract class

class WitWorld(WitWorld):

def add(self, a: int, b: int) -> int:

return a + b

Then you need to componentize this Python program:

componentize-py --wit-path adder.wit --world adder componentize guest-adder -o guest_adder_py.wasm

What is the difference between

guest_adder_py.wasmandguest_adder_rs.wasm?I was surprised to see that

guest_adder_py.wasmsizes much bigger thanguest_adder_rs.wasm, which we will come back later.

Guests and Hosts

Now we have compiled adder components from programs in Rust and Python, what then? As the adder components export one function, we should be able to call that function in our programs, like with libraries. In contrast to the notion of “caller” and “callee”, we use “guest” and “host”, because a host may need the offer from a guest (i.e., the exports of the component) while it may also provide capabilities a guest relies on (i.e., the imports of the component).

There are two ways to read the following content:

- you can read it sequentially, as it starts from basic examples to more involved ones.

- or, you can skip ahead by looking up the following table.

| Host/Guest | Rust Adder ↪ | Python Adder ↪ | Rust KVDatabase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rust Host ↪ | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ ↪ |

| Python Host ↪ | ✅ | 🛠️ | 🛠️ |

| Command Component (from Rust) | ✅↪ | 📌 | 📌 |

✅: Currently supported

🛠️: Not supported for now, under development of wasmtime-py

📌: TODO and welcome contributions

Rust Host

The implementation of a host is a bit complicated, so let’s take a look at the full code in Rust and then break it down.

We need latest wasmtime, which is the crate of the reference WASM runtime, and wasmtime-wasi, which provides utilities for running WASIp1 modules and WASIp2 components:

# in host-rs/Cargo.toml

[package]

name = "host-rs"

version = "0.5.2"

edition = "2024"

[dependencies]

anyhow = "1.0"

wasmtime = "38.0"

wasmtime-wasi = "38.0"

Before diving into the main logics, we need some utilities:

// in src/utils.rs

use anyhow::Context;

use wasmtime::component::{Component, Linker, ResourceTable};

use wasmtime::{Engine, Result, Store};

use wasmtime_wasi::{WasiCtx, WasiCtxBuilder, WasiCtxView, WasiView};

// reference: https://docs.rs/wasmtime/latest/wasmtime/component/bindgen_examples/_0_hello_world/index.html

// reference: https://docs.wasmtime.dev/examples-rust-wasi.html

pub(crate) struct ComponentRunStates {

// These two are required basically as a standard way to enable the impl of WasiView

pub wasi_ctx: WasiCtx,

pub resource_table: ResourceTable,

}

impl WasiView for ComponentRunStates {

fn ctx(&mut self) -> WasiCtxView<'_> {

WasiCtxView {

ctx: &mut self.wasi_ctx,

table: &mut self.resource_table,

}

}

}

impl ComponentRunStates {

pub fn new() -> Self {

ComponentRunStates {

wasi_ctx: WasiCtxBuilder::new().build(),

resource_table: ResourceTable::new(),

}

}

}

pub fn get_component_linker_store(

engine: &Engine,

path: &'static str,

alt_path: &'static str,

) -> Result<(

Component,

Linker<ComponentRunStates>,

Store<ComponentRunStates>,

)> {

let component = Component::from_file(engine, path)

.or_else(|_| Component::from_file(engine, alt_path))

.with_context(|| format!("Cannot find component from path: {path} or {alt_path}"))?;

let linker = Linker::new(engine);

let state = ComponentRunStates::new();

let store = Store::new(engine, state);

Ok((component, linker, store))

}

get_component_linker_store is the helper function we need, which creates a Component, a Linker<ComponentRunStates> and a Store<ComponentRunStates> all at once for us.

Component represents a compiled component that is ready to be instantiated while Linker is used to instantiate Components, linking components together as well as supplying host functionality to components. Store is conceptually a bit complicated. A Store is a collection of WebAssembly instances and host-defined state. All WebAssembly instances and items will be attached to and refer to a Store. For example instances, functions, globals, and tables are all attached to a Store. Instances are created by instantiating a WASM module (that resides in a component) within a Store.

For more details, see the documentations about

Component,LinkerandStore.

As for ComponentRunStates, it contains necessary fields to implement WasiView trait, which is essential for interacting with the functionalities provided by wasmtime_wasi.

If the above is a lot to take in, fear not. All you need to know for now is that all the code in src/utils.rs except my little helper function is basically standard to get started. You can take your time later to dig into the details of the wasmtime runtime.

With these utilities, we are ready to host a component. To synchronously call the add function of an adder component, we just need a few lines of code:

// in src/main.rs

use crate::utils::get_component_linker_store;

use wasmtime::component::bindgen;

use wasmtime::{Engine, Result};

bindgen!({

path: "adder.wit",

world: "adder",

});

fn main() -> Result<()> {

let (component, linker, mut store) = get_component_linker_store(

engine,

"./target/wasm32-wasip2/release/guest_adder_rs.wasm",

"./target/wasm32-wasip2/debug/guest_adder_rs.wasm",

)?;

let adder_bindings: Adder = Adder::instantiate(&mut store, &component, &linker)?;

let a = 1;

let b = 2;

let result = adder_bindings.call_add(&mut store, a, b)?;

assert_eq!(result, 3);

Ok(())

}

That’s it! The magic lies in wasmtime::component::bindgen macro, which generates bindings according to adder.wit at compile time.

You can run

cargo expand --bin host.rsto see the generated code bybindgen, which is sometimes necessary for debugging.

Note that bindgen can generate asynchronous bindings as well, which is useful when a component internally performs IOs like networking. Please refer to the async examples in wasi_mindmap.

Python Host

Hosting a component in Python is not well-supported yet, so we can run a small subset of components that don’t use any WASIp2 Resources. This for now also means we cannot run any components compiled from Python programs.

Follow this issue for updates.

Notwithstanding, we can still run simple components compiled from Rust programs.

First we will need to install wasmtime-py:

pip install -U "wasmtime>=38.0.0"

If you haven’t done so, compile the Rust adder component as mentioned in Adder Component.

With the Rust adder component, we need to generate Python bindings:

# replace guest_adder_rs.wasm with the path to your Rust adder component

python -m wasmtime.bindgen guest_adder_rs.wasm --out-dir adder_rs_bindings

This will create a Python package named adder_rs_bindings in the current directory.

To run the component, we can simply do the similar thing as in the Rust host:

# in run_guest_adder_rs.py

from wasmtime import Store

from adder_rs_bindings import Root

def run_adder_rs_guest():

store = Store()

adder_component_instance = Root(store)

result = adder_component_instance.add(store, 1, 2)

assert result == 3

print(f"{__name__}: 1 + 2 = {result}")

run_adder_rs_guest()

Or, with such a simple component, there’s a magic loader from wasmtime-py to load the component without generating bindings and run it:

# in run_guest_adder_rs_magic_loader.py

from wasmtime import Store

# The magic, refer to https://github.com/bytecodealliance/wasmtime-py?tab=readme-ov-file#usage

import wasmtime.loader

from guest_adder_rs import Root

def run_adder_rs_guest():

store = Store()

adder_component_instance = Root(store)

result = adder_component_instance.add(store, 1, 2)

print(f"{__name__}: 1 + 2 = {result}")

assert result == 3

run_adder_rs_guest()

Complications

So far so good. The above examples are simple and straightforward, except that we have a few points that were glossed over:

- Why exactly a Python host cannot run a Python component?

- Why does a Python component size much bigger than a Rust component?

- Why did we have a

interfaced_adder.witwhich is different fromadder.wit?

Before diving into these, please read through the Overview of WIT from WACMDoc, which is prerequisite for understanding the following sections.

OK, welcome back!

Standard Libraries

Let’s dive right into the first 2 questions.

According to the issue, wasmtime-py does not currently support running components build with componentize-py, because wasmtime-py does not yet support resources, which components built with componentize-py always use, as componentize-py unconditionally imports most of the wasi:cli world. ↪

The explanation is simple, but why does componentize-py unconditionally import most of the wasi:cli world in the first place?

We need to zoom more into the compiled component.

In the case of guest_adder_py.wasm, as we don’t need 3rd party libraries, the only logical parts in the module inside the component are Python’s std libs and our add logic. Because of the needs from Python’s std libs (e.g., handling crashes, reading env vars to modify the behavior of std libs), componentize-py unconditionally imports most of the wasi:cli world.

The batteries-included std libs of Python are huge, so the component size is much bigger than a Rust component, even though much of the std libs are not used in our adder example.

Therefore, the compiled component may be bloated by std libs:

- in terms of logics:

- std libs may include unused code in the component.

- std libs may also include useful code that we don’t explicitly require, like error handling.

- in terms of interfaces:

- std libs may include interfaces that we don’t need anyway

- std libs may require interfaces that we indirectly need, for example, stderr interface when a crash happens and error messages are printed.

A leaner language like Rust is no exception. For those who are interested, you can take a look at this issue in Rust repository, filed by me :) A brief summary of the issue is that when a simple functionality from Rust std is used, say the format! macro, the Rust compiler will include the whole wasi:cli world that includes some interfaces that are useless in this case, like wasi:cli/env for accessing environment variables.

Command Component from Rust and Compositions

We have tried running a component on a Rust and a Python host, but can we run a component on a WASM host? Yes and No.

We cannot run an adder component, say guest_interfaced_adder_rs.wasm, with wasmtime in command line, but we can run a command component with wasmtime in command line, for example:

wasmtime run command_component_hosting_adder.wasm

A command component is (just special) one that exports the wasi:cli/run interface, and imports only interfaces listed in the wasi:cli/command world, which allows it to be executed directly by wasmtime (or other wasi:cli hosts). ↪

For the purpose of demonstration, we will create a command component in Rust, which hosts an interfaced-adder component.

To create a command component with ease, we need some help from cargo-component.

# install cargo-component if you haven't

cargo install cargo-component

# create a new command component called `host-command-component`

cargo component new host-command-component

Inside the host-command-component project, you need to add the following content to Cargo.toml:

# other content omitted..........

[package.metadata.component.target]

# use the WIT file in the `wit` directory to define the world of this command component

path = "wit"

[package.metadata.component.target.dependencies]

# Replace the path below with the actual path to directory containing `interfaced-adder.wit`

"wasi-mindmap:interfaced-adder" = { path = "../guest-interfaced-adder-rs/wit" }

In host-command-component/wit, you need to add a WIT file for this command component, specifying its world:

// host-command-component/wit/host.wit

package wasi-mindmap:host;

world host {

import wasi-mindmap:interfaced-adder/add;

}

And then run cargo component check to generate bindings for interfaced-adder components. You will see bindings.rs in host-command-component/src/.

The main function of this command component is simple:

mod bindings;

use bindings::wasi_mindmap::interfaced_adder::add::add;

fn main() {

let result = add(1, 2);

println!("result: {}", result);

}

To compile this command component, run cargo component build. As of now, cargo-component still uses wasm32-wasip1 as the target (see the tracking issue), so you will find the compiled component in target/wasm32-wasip1/debug/host-command-component.wasm.

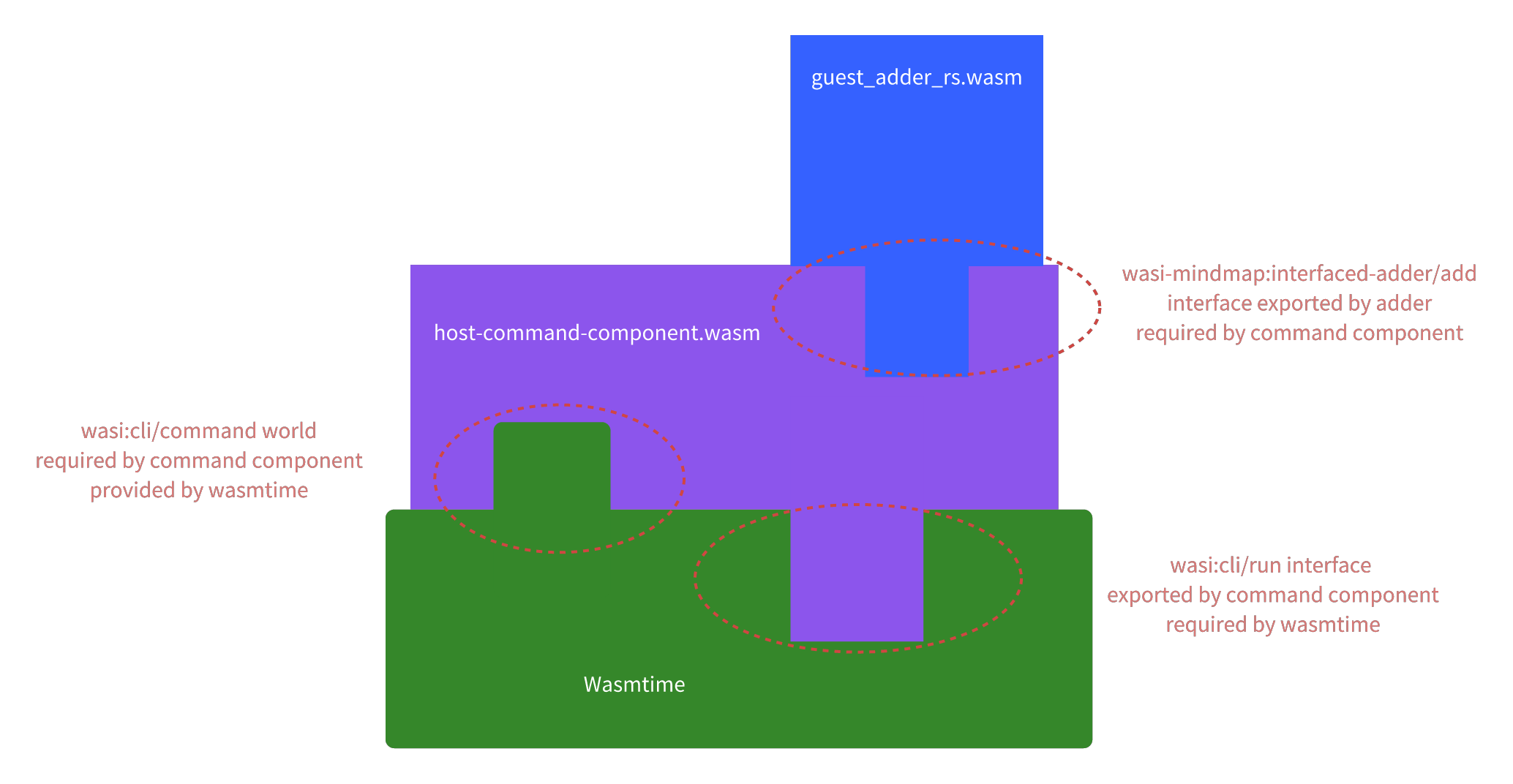

This command component imports the add interface from interfaced-adder component and the interfaces from wasi:cli/command world, and then calls the add function. What it exports is the wasi:cli/run interface. Therefore, you cannot run this command component with wasmtime in command line yet, because wasmtime does not have the add interface implemented.

What we can do is composition. We compose the interfaced-adder component with the host-command-component to form a new component, which imports only the wasi:cli/command interfaces and exports only the wasi:cli/run interface.

The “shapes” of individual components and the composed component.

The composed component is run by

wasmtimein command line.

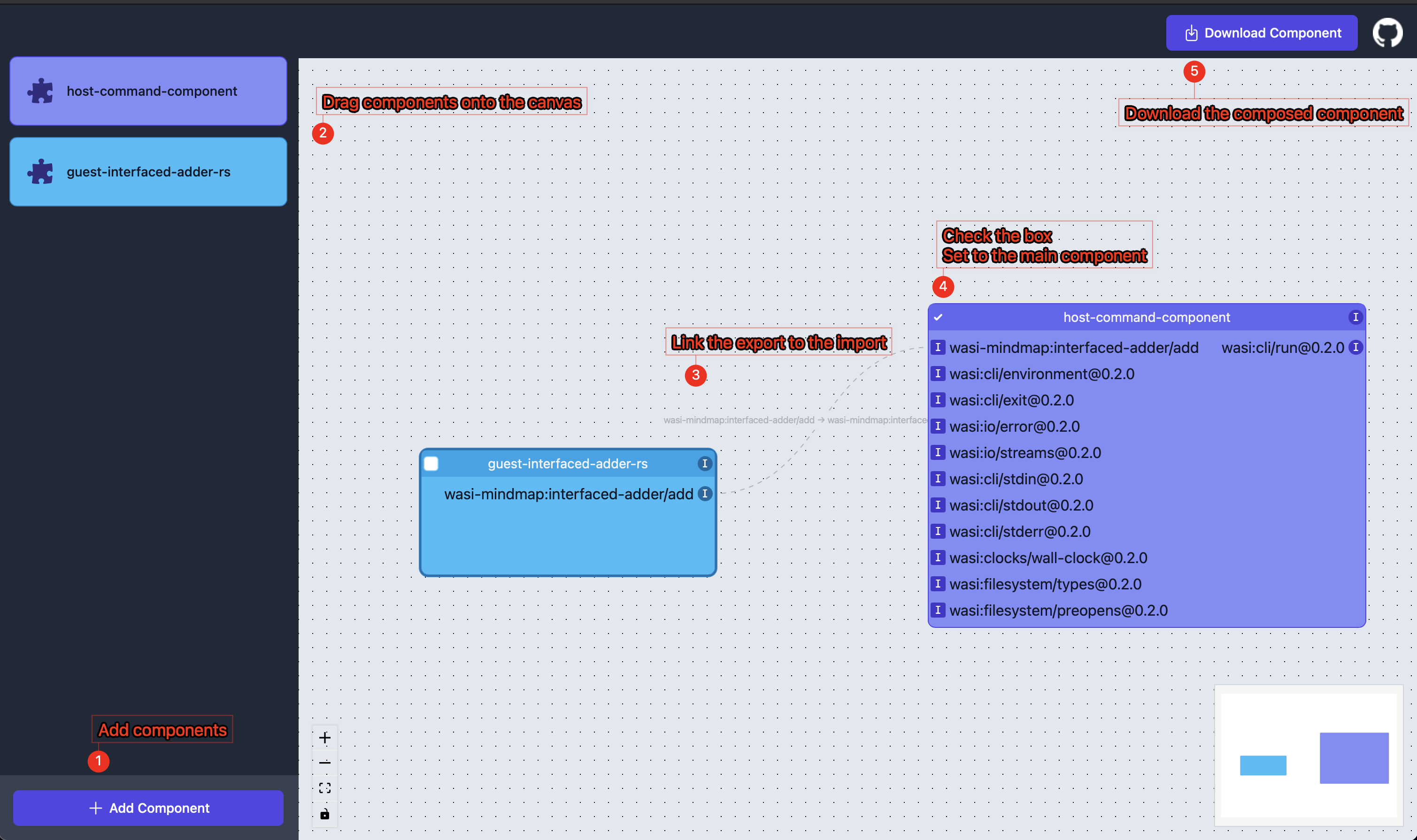

The composition can be done programmatically or visually with wasmbuilder.app. For the purpose of demonstration, we will use the visual way.

Please refer to Compose with WAC if you are interested in the programmatic way.

Compose with wasmbuilder.app

The steps are straightforward:

- Add components by uploading them.

- Drag them onto the canvas.

- Link the exported

addinterface to the importedaddinterface. - Check the box to set

host-command-componentas the main component. - Download the composed component with a name, say

composed-component.wasm.

Then finally, you can run the composed component with wasmtime in command line:

$ wasmtime run composed-component.wasm

result: 3

You can do such compositions with any compatible components, not just for a command component and a trivial adder component. This is where WASIp2 really shines. Imagine you have a Python component, a Go component and a C# component, as long as they have compatible import and export interfaces, you can compose them together to form a new component. This is a great relief if you have struggled with gluing programs via C ABIs.

Back to the question: Why did we have a

interfaced_adder.witwhich is different fromadder.wit?The composability of components is at the interface level. What we match against when composing components are the interfaces exported and imported by components, not the imported or exported functions. So, even though functions can be imported or exported at the top level of a world, they are not the unit of composition.

Host: Importing Interfaces at Runtime

In the Rust host example, we know that the magical bindgen macro generates bindings for the interfaces of a component at compile time. But what if we want to import interfaces dynamically at runtime? For example, fuzzing any components that have arbitrary interfaces.

wasmtime crate provides APIs for that, but the user experience is intentionally not good to discourage users from doing so. But, anyway, here’s a simple example:

pub fn run_adder_dynamic(engine: &Engine) -> Result<()> {

let (component, linker, mut store) = get_component_linker_store(

engine,

"./target/wasm32-wasip2/release/guest_interfaced_adder_rs.wasm",

"../target/wasm32-wasip2/release/guest_interfaced_adder_rs.wasm",

)?;

let instance = linker.instantiate(&mut store, &component)?;

let interface_name = "wasi-mindmap:interfaced-adder/add";

let interface_idx = instance

.get_export(&mut store, None, interface_name)

.unwrap();

let parent_export_idx = Some(&interface_idx);

let func_name = "add";

let func_idx = instance

.get_export(&mut store, parent_export_idx, func_name)

.unwrap();

let func = instance.get_func(&mut store, func_idx).unwrap();

// Reference:

// * https://github.com/WebAssembly/wasi-cli/blob/main/wit/run.wit

// * Documentation for [Func::typed](https://docs.rs/wasmtime/latest/wasmtime/component/struct.Func.html) and [ComponentNamedList](https://docs.rs/wasmtime/latest/wasmtime/component/trait.ComponentNamedList.html)

let ty = func.ty(&store);

// If you don't know the types of arguments and return values of the function at compile time

// iterate over the types of arguments at run time

for (i, p) in ty.params().enumerate() {

println!("Type of {i}th param: {p:?}");

}

// If you know the types of arguments and return values of the function at compile time

let typed_func = func.typed::<(i32, i32), (i32,)>(&store)?;

let (result,) = typed_func.call(&mut store, (1, 2))?;

// Required, see documentation of TypedFunc::call

typed_func.post_return(&mut store)?;

assert_eq!(result, 3);

Ok(())

}

You need to recursively get a handle (i.e., wasmtime::runtime::component::component::ComponentExportIndex) to an exported item (e.g., an interface, a function, a resource, etc.) from a component with an optional parent handle. For a function object (i.e., wasmtime::runtime::component::func::Func) that you get with a handle, you can iterate over the types of arguments and return values. If you know the types of arguments and return values at compile time, you can use Func::typed to get a TypedFunc object, which can be used to call the function with the types checked.

Conclusion

We have explored various axes of WASIp2 concepts and APIs:

- Implementations of hosts and guests

- Languages: Rust, Python

- Async and sync APIs: We’ve seen sync APIs in the examples while async examples are in the wasi_mindmap repository.

- Compile-time and runtime interface imports: We’ve seen compile-time interface imports using

bindgenand touched on runtime interface imports. - Standalone components and compositions

- Application complexity: We’ve seen simple adder examples while I leave a more complex example in the Appendix

With these, I hope this guide is more than a good start for WASIp2. Have fun hacking with WASIp2!

Issues and Contribute

Along my way stumbling through the WASIp2 tutorials, documentations and examples, I found a few issues and missing pieces, some resolved, some not:

- Resolved ones by me, just FYI:

- Unresolved ones, for those who may be interested in contributing:

As WASIp2 technologies are rather young, if you find WASIp2 is interesting, please consider contributing code and/or documentation to the related WASIp2 projects, like wasmtime and WebAssembly Component Model Documentation.

Finally, my code is also open sourced:

- wasi_mindmap: A collection of examples and tutorials about WASIp2.

- ideas reifying: The source of this blog site.

Contributions to my repos are also welcome!

Personal Notes and Beyond WASIp2

My motivation for using WASIp2 is to make modern software interops for large language models (LLMs) and autonomous agents. LLMs and agents can now solve difficult coding problems, and they will be much more capable very soon, but today’s softwares are very fragmented. The foundation of software interops is still legacy C ABIs, which are not only fragile but also dangerous. I can’t imagine how these (soon-to-be) super intelligence will be able to solve real-world software problems with today’s software interops, since we humans also suffer from the same problem.

Besides LLMs which may or may not end humanity, I also see some interesting explorations by us humans:

- Making WebAssembly and Wasmtime More Portable: This will enable

wasmtimeto run on more platforms, including mobile and edge devices.- In the use case of robotics, with WASIp2, we can run components (written in different languages) on a robot and/or MCUs of body parts of it while keeping them interoperable. This may be more powerful and flexible than Robot Operating System (ROS).

- k23: This is a OS kernel reimagined with WebAssembly. It leverages the built-in sandboxing of WebAssembly to provide a secure environment for running untrusted code. With WASIp2, programs (including the kernel) can be written in any languages with max interoperability and flexibility.

Appendix: More Examples

Here we have a more complex example - KV store.

package wasi-mindmap:kv-store;

interface kvdb {

resource connection {

constructor();

get: func(key: string) -> option<string>;

set: func(key: string, value: string);

remove: func(key: string) -> option<string>;

clear: func();

}

}

world kv-database {

import kvdb;

import log: func(msg: string);

export replace-value: func(key: string, value: string) -> option<string>;

}

As we don’t want to pass the entire KV store by value, we need to use resources. In this world, we need the interface kvdb to get a connection resource, and then use the connection resource to get/set/remove/clear values. The log function is also needed to log errors. The exported replace-value function is used to replace the value of a key, returning the old value if the key exists.

The implementation of the guest component in Rust is simple:

// guest-kv-store-rs/src/lib.rs

wit_bindgen::generate!({

// the name of the world in the `*.wit` input file

world: "kv-database",

});

struct KVStore;

impl Guest for KVStore {

fn replace_value(key: String, value: String) -> Option<String> {

let kv = wasi_mindmap::kv_store::kvdb::Connection::new();

// replace

let old = kv.get(&key);

kv.set(&key, &value);

old

}

}

export!(KVStore);

The host providing the kvdb interface and the log function is more complicated:

// main.rs

use crate::utils::get_component_linker_store;

use crate::utils::{bind_interfaces_needed_by_guest_rust_std, ComponentRunStates};

use std::collections::HashMap;

use wasmtime::component::bindgen;

use wasmtime::component::Resource;

use wasmtime::{Engine, Result};

bindgen!({

path: "../wit-files/kv-store.wit",

world: "kv-database",

with: {

"wasi-mindmap:kv-store/kvdb.connection": Connection

},

// Interactions with `ResourceTable` can possibly trap so enable the ability

// to return traps from generated functions.

trappable_imports: true,

});

pub struct Connection {

// use a hashmap to store key-value pairs

pub storage: HashMap<String, String>,

}

impl KvDatabaseImports for ComponentRunStates {

fn log(&mut self, msg: String) -> Result<(), wasmtime::Error> {

println!("Log: {}", msg);

Ok(())

}

}

impl wasi_mindmap::kv_store::kvdb::Host for ComponentRunStates {}

impl wasi_mindmap::kv_store::kvdb::HostConnection for ComponentRunStates {

fn new(&mut self) -> Result<Resource<Connection>, wasmtime::Error> {

Ok(self.resource_table.push(Connection {

storage: HashMap::new(),

})?)

}

fn get(

&mut self,

resource: Resource<Connection>,

key: String,

) -> Result<Option<String>, wasmtime::Error> {

let connection = self.resource_table.get(&resource)?;

Ok(connection.storage.get(&key).map(String::clone))

}

fn set(&mut self, resource: Resource<Connection>, key: String, value: String) -> Result<()> {

let connection = self.resource_table.get_mut(&resource)?;

connection.storage.insert(key, value);

Ok(())

}

fn remove(&mut self, resource: Resource<Connection>, key: String) -> Result<Option<String>> {

let connection = self.resource_table.get_mut(&resource)?;

Ok(connection.storage.remove(&key))

}

fn clear(&mut self, resource: Resource<Connection>) -> Result<(), wasmtime::Error> {

let large_string = self.resource_table.get_mut(&resource)?;

large_string.storage.clear();

Ok(())

}

fn drop(&mut self, resource: Resource<Connection>) -> Result<()> {

let _ = self.resource_table.delete(resource)?;

Ok(())

}

}

pub fn run_kv_store_sync(engine: &Engine) -> Result<()> {

let (component, mut linker, mut store) = get_component_linker_store(

engine,

"./target/wasm32-wasip2/release/guest_kv_store_rs.wasm",

"../target/wasm32-wasip2/release/guest_kv_store_rs.wasm",

)?;

KvDatabase::add_to_linker(&mut linker, |s| s)?;

// this is a special helper function, see the wasi-mindmap repo for more details

bind_interfaces_needed_by_guest_rust_std(&mut linker);

let bindings = KvDatabase::instantiate(&mut store, &component, &linker)?;

let result = bindings.call_replace_value(store, "hello", "world")?;

assert_eq!(result, None);

Ok(())

}

fn main() -> Result<()> {

let engine_sync = Engine::default();

run_kv_store_sync(&engine_sync)?;

Ok(())

}

This code example should give you a sense of how to implement a host and a guest with resources.

Metadata

Version: 0.2.1

Date: 2025.01.01

License: CC BY-SA 4.0

Changelog

2025.01.08: Updated tracking issues

2025.03.03: Updated to wasmtime >= 30.0 and fixed typos

2025.11.14: Updated to use latest code

2025.11.21: Updated to use latest wasmtime 39