Self-supervised Evolution: From Model Swarm to AGI

Self-supervised Finetuning, Model Swarm and Dynamic Utility Function will unlock the next-gen of AI training

Imagine you are developing an AI SaaS product for law firms, say a law agent, which helps search and analyse documents from clients. Because these documents are super sensitive and valuable, the clients are no way willing to send any of the contents to some remote servers. On-premises deployment is a must. Clients also want to be able to finetune the AI law model to tailor it exactly as they need. As a AI developer, you really need to improve your model over time to lead the game in a scalable way, presumably in a flywheel in which the more users, the faster the model can iterate. All without compromising users’ sensitive data.

When my boss told me something like this, I thought, well, it seems like we got to use some kind of Federated Learning. But this is an underdeveloped field with many complicated problems unsolved. How about just merging LoRAs that are periodically sent back from our close law firm partners? We can convince them that these LoRAs are anonymized data used to improve the model without any sensitive explicit data. However, their training objectives may be too niched and not align with ours, so the combination of these LoRAs may not yield a model that performs better on our general law eval set.

We need to somehow factor out the useful directions from these LoRA vectors. “useful” means improving the performance on our eval set.

Just a day later, by coincidence, I came across the Model Swarm paper. This is what I am going to discuss in the blog, not our law agent ambition.

With a few extensions, I believe the techniques in the paper can transform how we (post-)train AI models.

What is Model Swarm

I often find it interesting that different people understand a same articles quite distinctively, so below I have not one but three summaries.

First I asked Claude to help me out:

Can you please help me summarize this paper? I am writing a blog about it, but first I want to quickly summarize the key ideas of it.

Then, here’s what Claude thinks:

Key Ideas:

Core Concept:

- MODEL SWARMS is a collaborative search algorithm that adapts Language Models (LLMs) using swarm intelligence

- Multiple LLM experts work together to explore and optimize model weights guided by a utility function

- Inspired by Particle Swarm Optimization, where each LLM is treated as a “particle” moving through weight space

Main Benefits:

- Training-free: Works with as few as 200 examples, doesn’t require extensive fine-tuning data

- Assumption-free: Automatically discovers optimal model compositions without predefined rules

- Flexible: Can optimize for any scalar utility function (performance, rewards, human preferences)

How it Works:

- Starts with a pool of diverse LLM experts

- Each expert has a location (model weights) and velocity (direction in weight space)

- Experts are influenced by:

- Their own best previous position

- The group’s best position

- The group’s worst position (to avoid)

- Through iterative updates, experts collaboratively search for optimal weights

Key Results:

- Outperforms 12 baseline model composition methods by up to 21% across various tasks

- Works well on:

- Single tasks (knowledge, reasoning, safety)

- Multi-task domains (medical, legal, scientific)

- Reward model optimization

- Human interest topics

- Enables weak-to-strong model transitions: weaker models can become stronger through collaboration

Notable Findings:

- Diversity matters: More diverse initial experts lead to better results

- New capabilities emerge: Models discover abilities not present in any initial expert

- The best final model often didn’t start as the best performer

- Works with different architectures through “token swarms” variant

This novel approach offers a flexible, efficient way to adapt language models without requiring extensive training data or making assumptions about how models should be composed.

Also quoting the authors’ abstract:

We propose Model Swarms, a collaborative search algorithm to adapt LLMs via swarm intelligence, the collective behavior guiding individual systems. Specifically, Model Swarms starts with a pool of LLM experts and a utility function. Guided by the best-found checkpoints across models, diverse LLM experts collaboratively move in the weight space and optimize a utility function representing model adaptation objectives. Compared to existing model composition approaches, Model Swarms offers tuning-free model adaptation, works in low-data regimes with as few as 200 examples, and does not require assumptions about specific experts in the swarm or how they should be composed. Extensive experiments demonstrate that Model Swarms could flexibly adapt LLM experts to a single task, multi-task domains, reward models, as well as diverse human interests, improving over 12 model composition baselines by up to 21.0% across tasks and contexts. Further analysis reveals that LLM experts discover previously unseen capabilities in initial checkpoints and that Model Swarms enable the weak-to-strong transition of experts through the collaborative search process.

My Interpretation and Thoughts

When I finished reading the paper, my feeling was although the abstract practically summarizes authors’ contribution, it understates some key points that may be of greater impact when extrapolated from large language models (LLMs).

Below are what I consider as key points that worth more highlights (in the following paragraphs in bold italics).

Upon reading it, with a basic understanding, two questions came to my mind:

- How does it synchronize the optimization?

- Where are gradients?

It turns out that these two are very helpful for understanding the algorithm and extrapolating it.

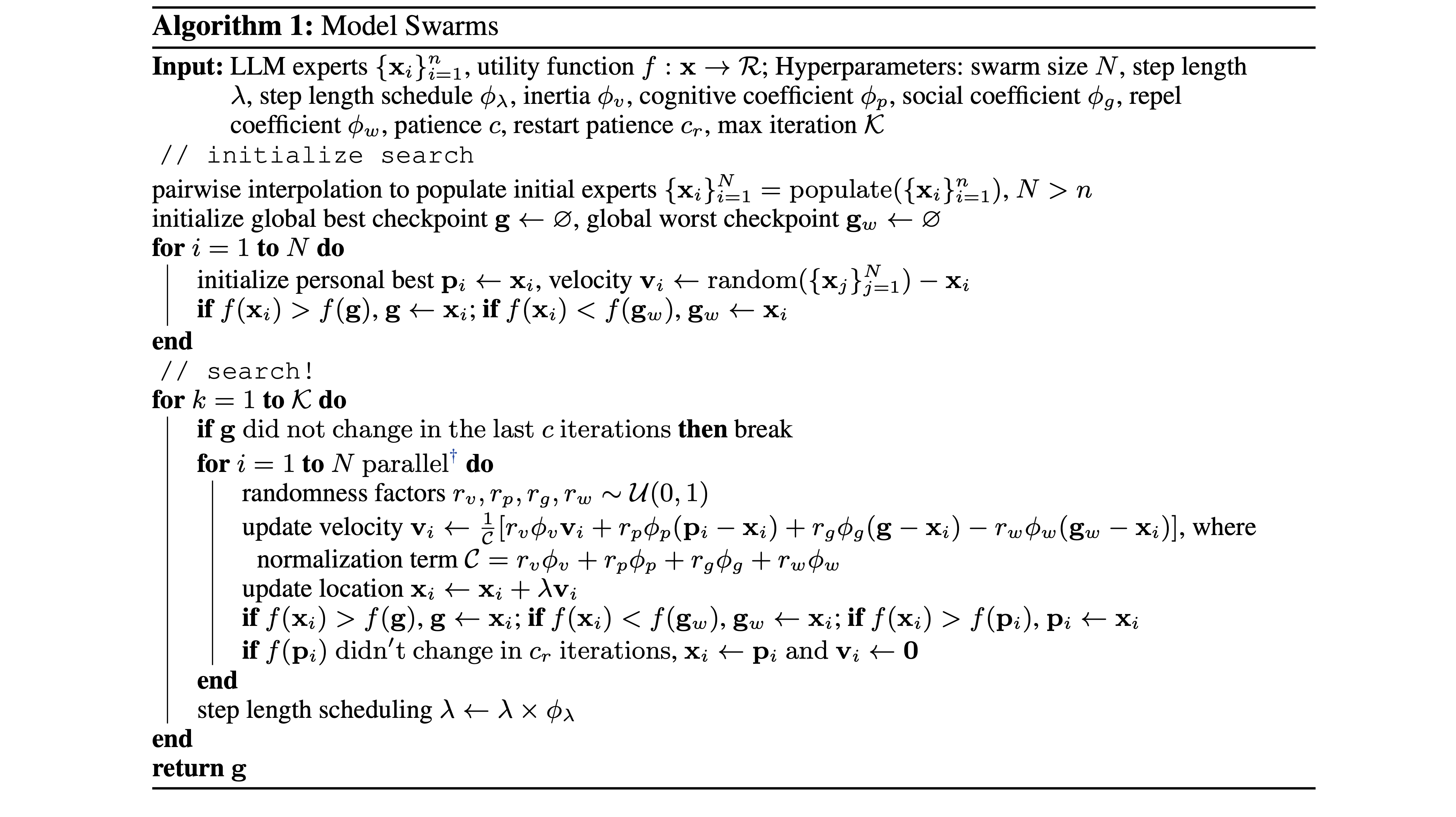

In essence, with a bit radical simplification, this algorithm scatters particles (different LLM experts) onto the optimization landscape (i.e., the high-dimensional parameter space). The height of the landscape is given by the utility function 𝑓. In each iteration, every particle is evaluated by height. Every one is led towards the current highest one g, which is the current global best, also considering their path and the current global worst g_w.

This is very similar to backpropagation or gradient-based optimization, but there is no gradient. Wellknown is that in distributed training, backpropagation incurs a lot of synchronization overhead, which is perhaps the biggest problem in scaling a model and training process.

Without backpropagation, assuming we don’t need synchronization, we could scale training/optimization “without limits”. So, where is synchronization in this algorithm? And I pray for not finding it.

As I squeeze my eyes, I sadly found the synchronization points (SPs) :

Exchanging the utility scores (i.e., 𝑓(x_i)) needs one synchronization: “Who gets the highest score (role-model) and who gets the lowest score (anti-role-model) in this iteration?”

Exchanging the weights of the role-model and anti-role-model is one expensive synchronization, as the weights are needed in updating velocities.

IF the evaluation of the utility function 𝑓 is centralized, we also need to send weights of all models to an exchange point, which we shall call “Weight eXchange Point (WXP)” :) Sending weights and evaluating 𝑓 also needs synchronization.

Leaving aside synchronization, however, the authors inadvertently tackle SP.1 and SP.2 via two experiments:

Dropout-K/N:

Quoting “randomly skipping model evaluation in d_k % of iterations or for d_n % of experts”. This effectively simulates that d_k % of iterations are out of sync and that d_n % of experts are out of sync. Their results, translated in terms of synchronization, indicate that even if synchronization of a model swarm is not guaranteed, there are still improvements, which gives us some hope that maybe, even if all experts were updated asynchronously, they could still contribute to the whole.

Token Swarms:

The authors wanted to generalize the method to experts with different architectures, but they unintentionally attacked SP.2 in the meantime. Instead of exchanging the full weights of the role-model and anti-role-model, the token swarm matrices are exchanged, which manipulate the next-token probability distributions of experts. These matrices have a lot fewer parameters, which makes the synchronization a lot cheaper, at the cost of less improvement though.

From the technical perspective, SP.3 is trivial to solve. We can assume every distributed nodes, which optimize different experts locally, to be trustworthy ones that compute 𝑓 locally and report the scores to everyone.

Besides, by having experts maintain their own trajectories while being guided by global signals (g and g_w), the algorithm effectively factors out generally useful weight updates while filtering out specialization noise. With this, when merging specialized LoRA vectors from our lawyer friends - instead of naively combining weights, we can use the utility function f to identify beneficial directions in the weight space while preserving individual specialization through personal trajectories.

Finally, the results of this paper re-affirms that models can generalize from specific tasks and emerge new behaviors and that specialized individuals can learn from each other to assemble a better whole. This generally aligns with the findings in Multimodal Pathway.

What’s the big deal

So, besides the highlights in the abstract, the paper also features:

- Gradientless Optimization

- A few SPs that can be (partially) mitigated, which might enable distributed asynchronous training

- A mechanism to factor out generally useful weight updates while filtering out specialization noise

- Reaffirmation of the generalizability of LLMs from specifics

What’s the big deal? Let’s take some examples, which are likely to evolve into AGI!

Case 1: Autonomous Driving

The HW4 on Tesla cars is estimated to have an accelerator of 50 TOPs. There roughly are 1.2 million units of Model Y sold in 2023, according to Wikipedia. So simple math gives the total compute power of these cars is 60 Exa-OPS, while the fastest supercomputer to date offers 1.1 Exa-Float-OPS.

What if we used all this compute power to train an autonomous driving model? You may also have heard the similar from a super famous guy :)

With Model Swarm, this idea might not be that unrealistic! A Tesla car initially has a same trained model x_p, but with the shadow mode, over time, the on-car model is trained locally, learning from the driver. After some time, x_p gets trained into a finetuned/specialized model x_i (i.e., an expert or a particle in the swarm). Even if x_i learns unsafe driving from a risky driver, the utility function 𝑓 scores safe-driving models higher. Periodically, the parameters of x_i, g and g_w can be exchanged via OTA channels.

With a bit ambitious imagination, it’s not so hard to apply Token Swarms to autonomous cars, even if they are manufactured by different car companies, since the action space of driving pretty much is already a consensus.

Case 2: Next-frame Prediction and World Models

In autonomous driving cars, there’s a module or a neural network that, given history and current observation, tries to predict the near future, like the next frames or world states. In the realm of AI content generation, video generation models can generate plausible future frames given a few frames and/or a text as prompts.

Arguably, a model capable of accurately predicting future frames is essentially modeling the world. We can train a “world model” by tasking it to predict future frames. This task can be fully self-supervised, meaning the training data need no human annotations.

When such a world model is deployed on a device (e.g., cars, robots, drones), it’s a same trained model, but then it will be trained continuously in our physical world, observing partially of the 4D space-time. It will become an expert in a 4D fragment of our world. Then, these world models exchange their partial learning through SPs and good (measured by 𝑓) world models get “famous” and influential.

We, as individuals, are also experts in 4D fragments of our world. Think about your neighborhoods. You can roughly imagine what will happen down the street at a specific time. And you know what it used to be. At the meantime, you may not be very familiar with a place years ago or miles away. Our mental world models covers a little fragment on the earth and an even smaller fragment in the history. However, we can also exchange information with each other or from news, so we know some gossips of someone, some wars in some countries, etc.

Self-supervised Finetuning

There’s one thing I intentionally gloss over in the above example, which is data collection/training schemes. I think of data collection and training schemes as the two sides of a coin. Obviously, in the large scale of the two example, we just simply can’t afford supervised learning/finetuning. We can’t ask millions for people to annotate data for their cars. So, we need to do self-supervised training/finetuning without explicit human efforts.

By self-supervised finetuning (SSFT), I mean we can automatically collect data for continuously optimize a pretrained model.

“pretrained” is emphasized because we don’t want to train a model from scratch in such a distributed asynchronous setting. Centralized gradient-based training is simply more efficient, so use it to pretrain a model.

Automation is defining. This is more general that the definition of self-supervised learning. Self-supervised learning is often implemented as mask-and-predict or next-X prediction.

However, I’d include reinforcement learning and reflection-based bootstrapping (like below) into the category of SSFT:

Say, we have a conversation with a LLM:

User: 9.11 and 9.9, which one is bigger? LLM: 9.11 is bigger. User: OK, let me clarify. I was not talking about chapters of the Bible nor a date\*. I mean numbers. LLM: Sorry. Number 9.9 is bigger than 9.11Then we have a reflection mechanism using the same LLM or a critic mechanism with a more powerful model to automatically collect data:

System: based on the above conversation, do your reflection and try to give a better answer in the forms of Q&A ……… LLM: (some reflection followed by revised Q&A) ``` User: 9.11 and 9.9, which one is bigger? LLM: Mathematically 9.9 is bigger than 9.11. But if you were talking about a date or chapters of the Bible, 9.11 is bigger. ```Thus we have automatically got a new and better datum for finetuning this LLM.

* FUN FACT: Check out the insightful work done by Transluce!

In Case 1, SSFT is done by collecting human data when drivers manually drive their cars. The collection needs no explicit human effort (unless the driver is paid to drive solely for collecting data). In Case 2, SSFT is done by next-X prediction. To collect data, we can just leave camera on indefinitely.

Lifelong Learning with Dynamic Utility Function

I think the utility function is a powerful and generalizable tool to nudge the evolution of the swarm of experts. As mentioned in the paper, the scores of 𝑓 can be the performance on a dataset, ratings from reward models, or human preferences. But it’s more than any of these:

- Compared to eval set performance, 𝑓 implicitly nudges the weights of experts by selecting a good one and a bad one to be influencers that others can directly learn from (see the velocity update formula).

- While rewards and 𝑓 scores both indirectly provide feedbacks, the feedback from 𝑓 is denser because of the terms (g - x_i) and (g_w - x_i) , instead of probabilistic estimates.

- Clearly this evolution-based mechanism is more generalizable and scalable than human rating.

- 𝑓 can be a mixture of these.

Our world is constantly changing. I don’t think a world model can be AGI if it cannot adapt to the dynamics of our world. So, it requires lifelong learning capabilities - arguably as crucial a goal as achieving static artificial superintelligence.

While in the paper 𝑓 is static, it can dynamically evolve just like the evolution itself. For example, if 𝑓 is eval set performance measure, we can gradually introduce new a eval set by setting weights, thus selecting new role-models and anti-role-models to “lead” experts to explore new space. This is naturally analogous to human behaviors. Optimization landscape is shaped by 𝑓, so when 𝑓 changes, the optimization landscape reshapes and the inhabitants (i.e., experts) unsettle. Similarly, we humans gradually inhabit new places when natural landscape changes over decades. And natural selection’s “fitness function” isn’t static but changes with environmental conditions. In contrast, it’s neither effective nor helpful to change eval set when a model is under gradient-based training.

Dynamic Utility Functions (DUF) may pragmatically solve a question that’s been haunting many (including me):

What do we do when we run out of eval sets or benchmarks?

Or, equivalently “what is the eval set for an artificial superintelligence?”

With a DUF that is constantly evolving, we might resort to the answer “We don’t definitely know, but we can always improve our utility function and then the intelligence will align with it”.

Yet, the effectiveness of DUF is still unclear, as the authors didn’t experiment with it in the paper. This is solely my idea.

Self-supervised Evolution

I think the combination of Model Swarm, SSFT and DUF can be the next big thing in training AIs, so I term it Self-supervised Evolution, emphasizing the importance of self-supervised learning and the dynamic evolution nature of Model Swarm.

Self-supervised Evolution = Model Swarm + Self-supervised Finetuning + Dynamic Utility Function

Ending

Giant companies are burning billions of dollars to develop next AIs. As a computer scientist, I understand why they have to technically centralize compute power, but I don’t like the cyberpunk future. Also, this centralization and synchronization seems unnatural to me, since this is not how nature works. Nature runs in asynchrony and nature is a distributed system.

With the techniques from Self-supervised Evolution, AIs could be again tuned on-device. The world they, as a whole, see is more complete and dynamic. I hope AI can be unchained from racks of servers, helping individuals to break theirs too.

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to Claude for the summary, reviewing this blog and giving insightful ideas!

Metadata

Version: 0.0.2

Date: 2024.10.28

License: CC BY-SA 4.0

Changelogs

2024.10.28: A few wording changes